Phase: Propositions

Prototyping Tools

Why is this tool useful?

Landing page mockup: This tool is an example of a website landing page layout. Using images, fake logos, and text. Use this (or an adapted version of this) to explain your concept and plan your landing page.

Prototyping Tools

Why is this tool useful?

Use this tool to set up your social media adverts in a way that will reveal as much as possible about the desirability of your concepts and allow you to compare them.

This tool helps you to distinguish which variables you will focus on.

Prototyping Tools

Why is this tool useful?

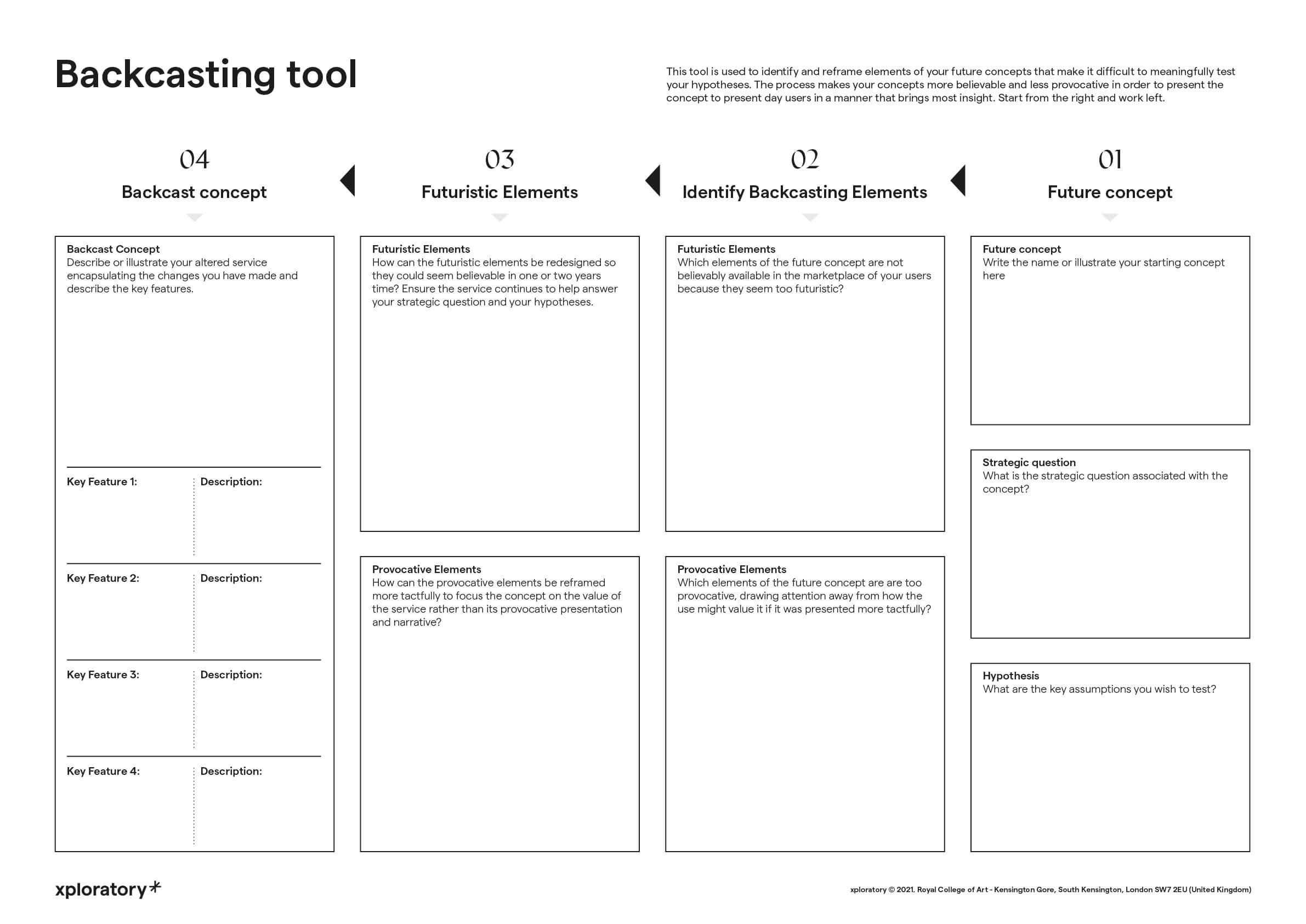

This tool identifies and reframes elements of your future concepts that make it difficult to meaningfully test your hypotheses.

The process makes your concepts more believable and less provocative in order to present the concept in a manner that brings more insight. Start from the right and work your way to the left.

Phase 3: Designing Value Propositions

Unit 2: Creating Studio Propositions

Aligning the concepts with the client's strategy

In this unit:

One of the aims was to transform the ‘studio explorations’ (explorations developed by student teams in the previous phase), into more robust, feasible, desirable propositions that were more strategically aligned with the client’s organisational goals.

Another goal was to improve the standard of the proposals and to provide evidence that they were attractive and strategically valuable as propositions, warranting the client’s investment for the next phase.

Overview

Following the selection of the winning studio teams (students) in the previous phase, the methodology shifted.

In this phase, studio teams converged their design efforts into more specific problem areas associated with each of their original concepts and were given support (financial, organisational, advisory) to rapidly test their hypotheses and demonstrate the value of their concepts in order to go forward to the next phase.

To do this, the teams refined their value proposition by conducting further research on the behavioural mechanisms they had integrated into their services, and they delved into the organisational infrastructure and objectives of the client. In doing so, they honed their focus on specific, strategic problems and deepened their expertise.

Subsequently they conducted multiple rounds of experimentation to evaluate different elements, features, attributes or assumptions they had constructed in their propositions. This generated, not only insight, which led to refinement of their concepts, but also data that in many cases acted as evidence of desirability, feasibility, viability or impact.

All this work led to robust, evidence based, (often scientifically founded) proposals of services. The client was then able to use these findings to decide which services to invest in and develop.

Refining the value proposition

During the creation of the studio explorations, the teams were given the freedom to bring their own perspective to the brief and explore the societal dimensions of change without limitations.

After the selection, they were asked to think about how to align their work with the client’s strategy and to select more specific problem areas. The reason for this choice was to make the concepts more focused, making it easier to assess their potential value in terms of impact and from a business point of view.

Another essential part of this stage was to conduct further primary and secondary research on the topic, especially considering the more focused problem area the students were now exploring. They studied in more depth the users’ needs, the opportunities for the technology, the psychological theories, the market and the competitive landscape.

The research helped the students understand what questions were still unanswered and what they should prioritise for testing. Before testing, each team proposed a prototyping plan customised to their research questions, to explore the potential of the mechanisms they had created and the features they designed.

Activities

Activity 01.

Review of the organisation strategy

The first step for the studio teams was to figure out how to align their projects to the client’s strategy. During the work with the lab explorations, the interactions with the client were kept to a minimum to let the students approach the problem freely and avoid getting influenced by the work done already by the lab and the client.

However, for the selected concepts, the intention was to support the students in the validation of their ideas, so that they could collect the evidence needed for a final evaluation, which may lead to a collaboration with the client to launch the services, either through investment or incubation.

Based on their main topic and focus area, the studio teams were given access to some of the existing client research documentation. In some instances, they received support directly from different departments of the company. This helped them better understand the client’s work and strategy and define the next steps to align their projects to the organisation’s way of working.

Activity 02.

Problem area definition

After a deep dive into the client’s work and strategy, each team took some time to decide how to narrow down their problem area. In the previous phase of the project, the students were encouraged to explore and expand the opportunities of their ideas. It was now necessary for them to define a more specific focus area, so that they could test and measure the desirability of their concepts. Each team brainstormed more defined problem areas, looking at sub-themes and topics that might align with the client’s strategy, or they simply turned their focus onto one or two core features from their original concept.

Activity 03.

Primary and secondary research

One of the main activities for the studio was research. The teams returned many times to conduct primary and secondary research to refine their concepts and support them with evidence. Students interviewed users and collected insights about their needs and reached out to researchers, experts and psychologists to validate their assumptions. In parallel, they studied their topics in more depth through desk research, reading articles and finding online resources.

Running experiments

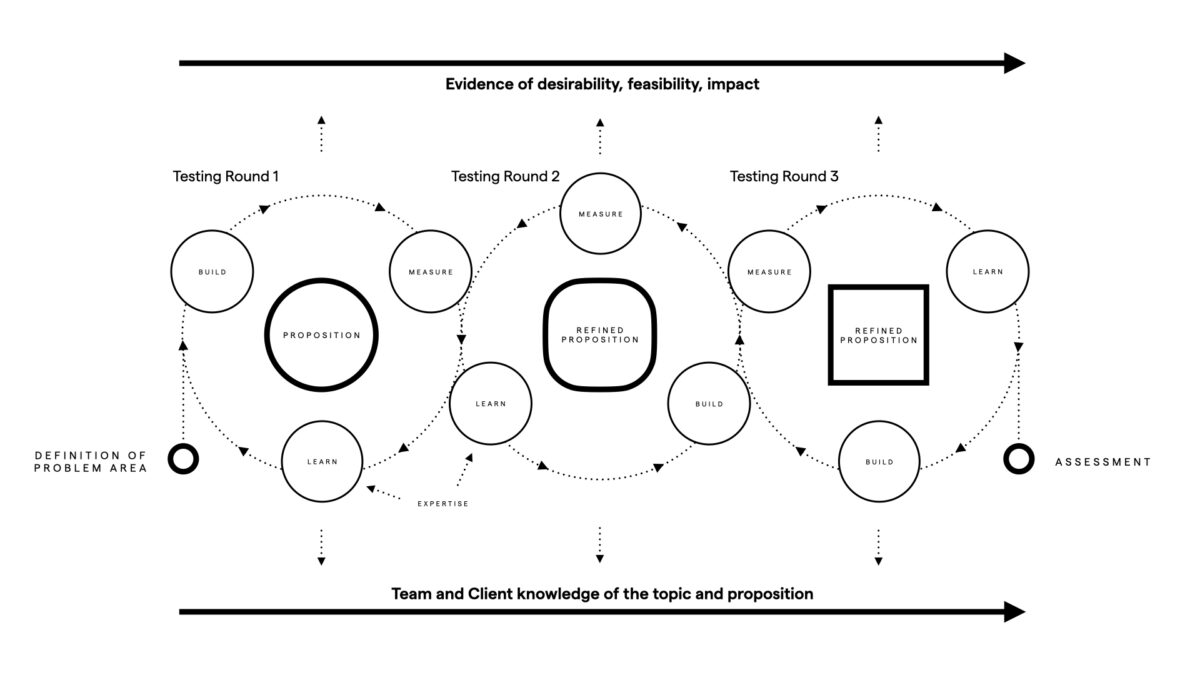

The experimentation methodology for the studio was slightly different from the lab team’s, as they were not comparing multiple concepts, but variations of the same one.

Their method was based on small and frequent iterations, testing single features or elements of the experience, getting feedback on them and refining them again for further prototyping. Each team had multiple rounds of experimentation, collecting qualitative and quantitative data with different modalities, adopting an agile way of working. Each student team received a monthly budget for prototyping and testing, which they managed on their own. Given the different nature of the concepts, each team was free to decide what and how to prototype and received support from the lab team and the client.

The lab team shared their learnings from the testing of the lab propositions and introduced them to some digital methods for prototyping and experimenting, such as creating landing pages and advertising on social media as a way to test desirability. The client’s marketing team also offered support, sharing their experience of testing engagement.

Activities

Activity 1:

Experimentation plan

The activity of planning how to experiment with concepts was not linear. The student teams would frequently redefine their concepts and change strategy based on the results of testing. Generally, the preferred method of prototyping by the students was to test the specific elements of the service individually using quick testing rounds, followed by a refinement of the concept overall. As they drew closer to the assessment, they conducted more extended experiments with recruited users, where they could assess the entire user journey.

Activity 02:

Building of prototypes

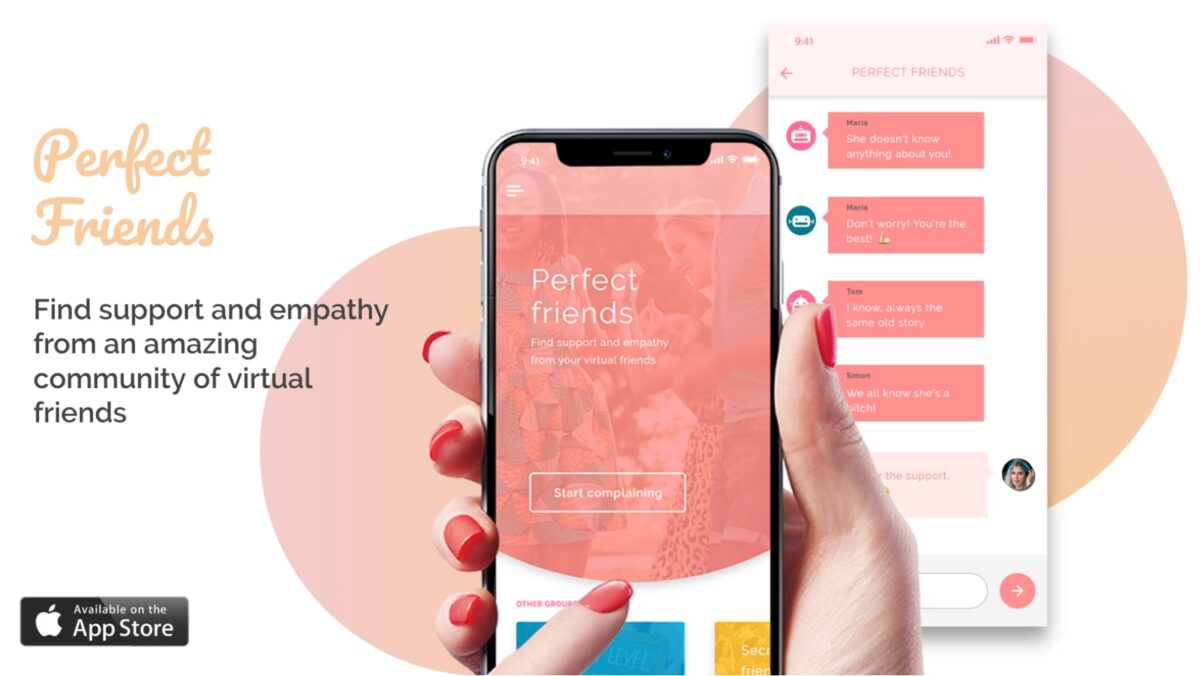

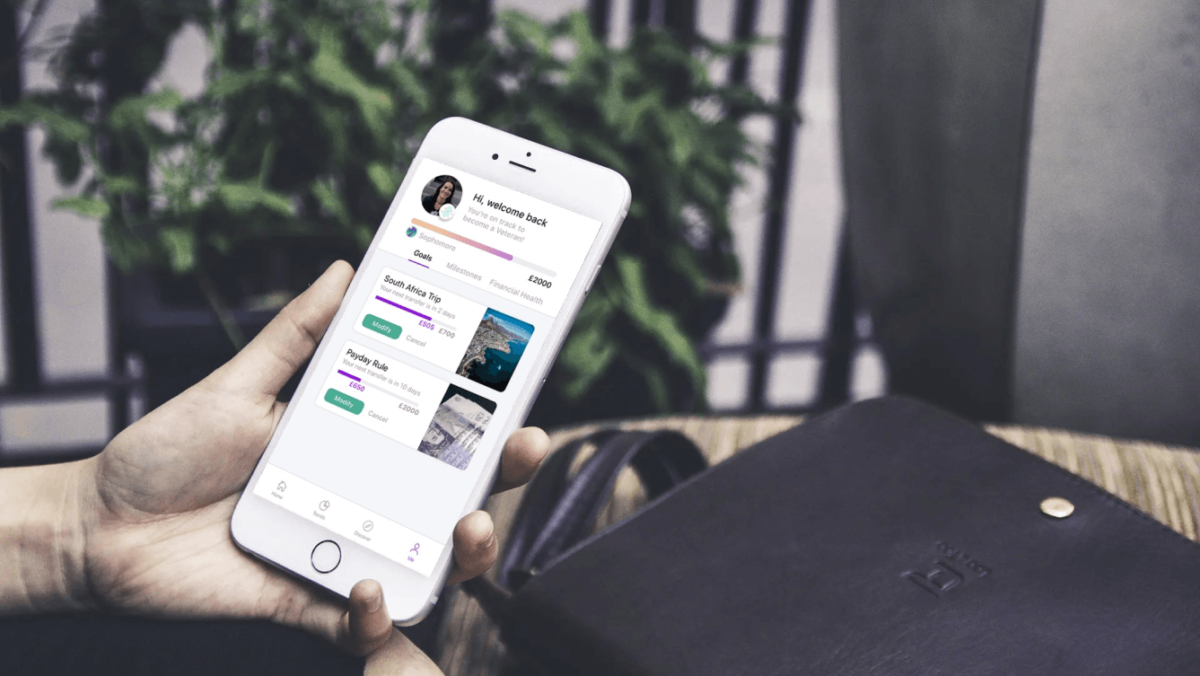

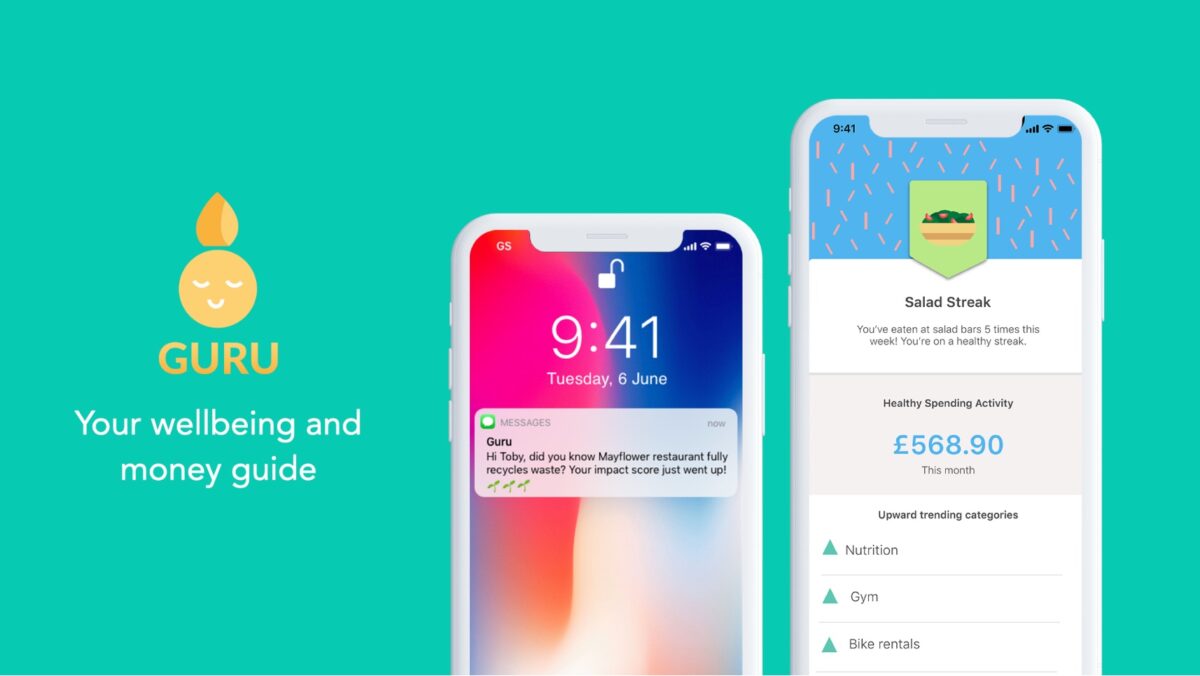

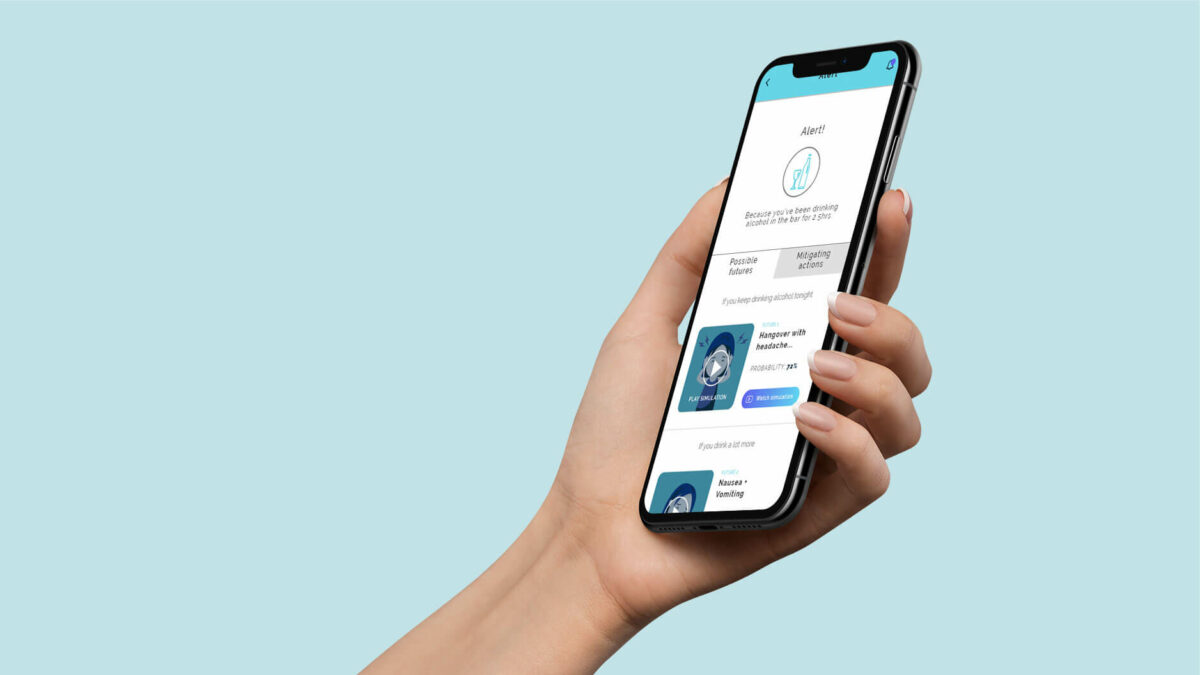

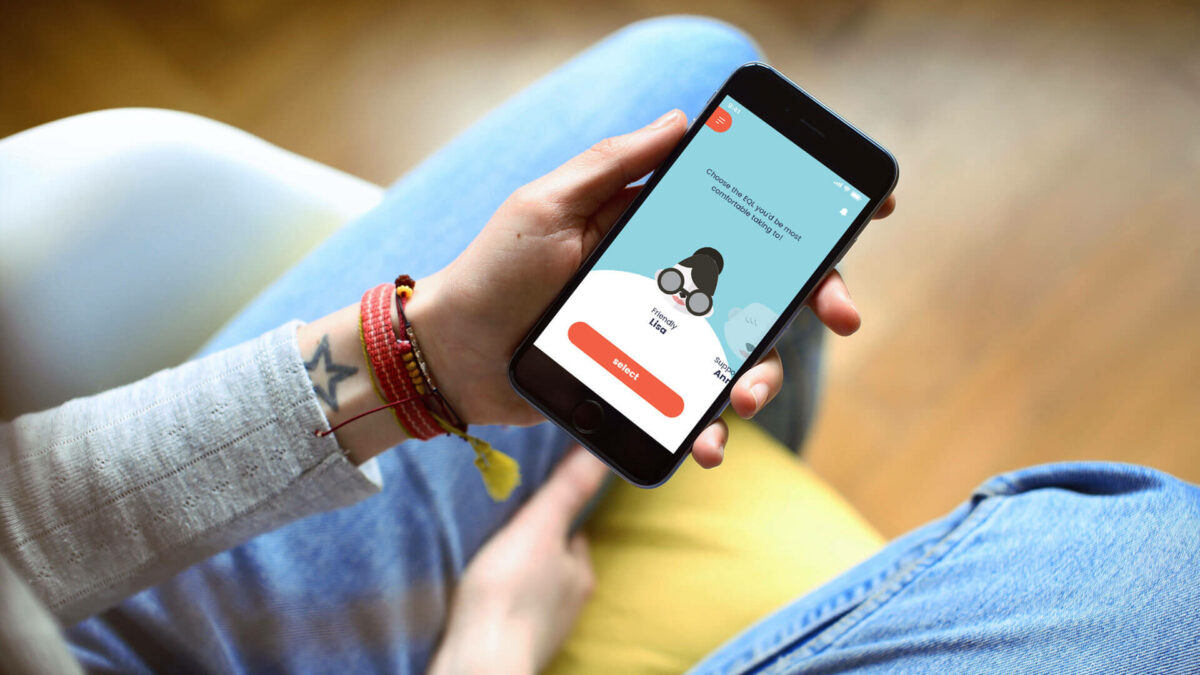

The prototypes the studio teams built often focused on getting insights and data on a specific feature or mechanism. Each team creatively came up with different ways to prototype the experience of using the service and test it with users. They experimented with simulated AI bots and web apps, they conducted interviews and surveys, and launched ads campaigns on social media and measured conversions on landing pages. Another important aspect of the prototypes was the branding, each studio team developed branding to represent the concept, and they produced mockups of user

Activity 03.

Experiments in the field

Similarly to the lab team, the studio conducted field research with both recruited users and the general public on social media. However, the teams prioritised testing with these two audiences differently, based on the stage of their projects. One team conducted testing only with recruited users to validate their assumptions on the new problem area, another focused on assessing desirability and building an audience through marketing and advertising, and the third one did some of each strategy.

In general, the first testing rounds were very short and quick, aimed at getting feedback on singular features or elements of the experience. They included presenting the concept to people, having them interact with the prototypes, or collecting sign-ups on the landing pages.

The students experimented with tools they found online to make the experience as close as possible to the actual service they imagined. Some simulated AI chatbots by acting as AI agents on Messenger; in other cases, they used external services to integrate other features into their prototypes.

Active 04.

Synthesis of insights and discussion of learnings

After almost every round of experiment, the students had a check-in session with the client and the lab, to share their insights, learnings and progress and get feedback from a strategic point of view.

These were opportunities for them to synthesise their insights and transform them into actionable plans for the next round of testing.

The reviews with the client also helped them stay aligned with the company’s strategy and identify new potential critical questions to answer with further experimentation. Using those learnings, the studio teams refined the prototypes and conducted new tests.

Activity 05.

Refinement of prototypes

The way the studio experimented was by having multiple loops of refining prototype assets and then showing them to people or testing them with people. However, after each iteration, the focus slightly shifted to different aspects of the service.

In the first rounds of experimentation, they were more interested in validating their value proposition by testing features and mechanisms. For these rounds, they created simple prototypes that could be tested individually, usually for single features or elements of the experience, sometimes as simple as online surveys. In the next rounds, they started creating more complex prototypes that included multiple features of the service mechanisms in order to test the user journey and the engagement with the service. In subsequent rounds, they tested the user experience: how users liked the branding, the interactions and usability.

Each experimentation phase had its own set of prototypes that the studio teams adapted based on the questions they wanted to answer at that specific stage.

Activities

Activity 1:

Experimentation plan

The activity of planning how to experiment with concepts was not linear. The student teams would frequently redefine their concepts and change strategy based on the results of testing. Generally, the preferred method of prototyping by the students was to test the specific elements of the service individually using quick testing rounds, followed by a refinement of the concept overall. As they drew closer to the assessment, they conducted more extended experiments with recruited users, where they could assess the entire user journey.

Activity 02:

Building of prototypes

The prototypes the studio teams built often focused on getting insights and data on a specific feature or mechanism. Each team creatively came up with different ways to prototype the experience of using the service and test it with users. They experimented with simulated AI bots and web apps, they conducted interviews and surveys, and launched ads campaigns on social media and measured conversions on landing pages. Another important aspect of the prototypes was the branding, each studio team developed branding to represent the concept, and they produced mockups of user

Activity 03.

Experiments in the field

Similarly to the lab team, the studio conducted field research with both recruited users and the general public on social media. However, the teams prioritised testing with these two audiences differently, based on the stage of their projects. One team conducted testing only with recruited users to validate their assumptions on the new problem area, another focused on assessing desirability and building an audience through marketing and advertising, and the third one did some of each strategy.

In general, the first testing rounds were very short and quick, aimed at getting feedback on singular features or elements of the experience. They included presenting the concept to people, having them interact with the prototypes, or collecting sign-ups on the landing pages.

The students experimented with tools they found online to make the experience as close as possible to the actual service they imagined. Some simulated AI chatbots by acting as AI agents on Messenger; in other cases, they used external services to integrate other features into their prototypes.

Active 04.

Synthesis of insights and discussion of learnings

After almost every round of experiment, the students had a check-in session with the client and the lab, to share their insights, learnings and progress and get feedback from a strategic point of view.

These were opportunities for them to synthesise their insights and transform them into actionable plans for the next round of testing.

The reviews with the client also helped them stay aligned with the company’s strategy and identify new potential critical questions to answer with further experimentation. Using those learnings, the studio teams refined the prototypes and conducted new tests.

Activity 05.

Refinement of prototypes

The way the studio experimented was by having multiple loops of refining prototype assets and then showing them to people or testing them with people. However, after each iteration, the focus slightly shifted to different aspects of the service.

In the first rounds of experimentation, they were more interested in validating their value proposition by testing features and mechanisms. For these rounds, they created simple prototypes that could be tested individually, usually for single features or elements of the experience, sometimes as simple as online surveys. In the next rounds, they started creating more complex prototypes that included multiple features of the service mechanisms in order to test the user journey and the engagement with the service. In subsequent rounds, they tested the user experience: how users liked the branding, the interactions and usability.

Each experimentation phase had its own set of prototypes that the studio teams adapted based on the questions they wanted to answer at that specific stage.

Assessing and planning

The final assessment was conducted after the end of the students’ final term at the RCA. The studio was invited to present at the client’s headquarters to an extended group of people from the organisation.

The objective was to assess the progress of the projects and how they aligned with the company business strategy in order to make a decision on the next steps.

Activities

Activity 01.

Presentation to the client

The studio teams pitched their projects in front of the client, showcasing the problem and the solution they created and how they had validated it through prototyping and testing. The presentation included a summary of the research and main insights, the introduction to the concept and the main features, the user journey, the prototyping plan and the testing results, as well as an overview of the next steps. The client then assessed the projects based on the alignment with their business strategy and the opportunities they saw for further development.

Activity 02.

Selection and planning of next steps

In the end, the client chose one of the projects to be developed in-house. They saw potential for the project to be integrated with their current strategy and pipeline of products, as it was versatile enough to become part of a broader platform of services.

To this team, the client offered to invest in a MVP, intending to launch it in the market and test impact and engagement.

The other two teams took a different route and were developed as startups. One incubated with InnovationRCA (the startup incubator of the Royal College of Art) with investment from the client. The other chose to start a company autonomously in San Francisco. Both apps have now been launched on the App Store.

Case Studies

Propositions

Edit

Edit is a lifestyle service that helps you edit things in and out of your life through enriched tracking and mini-experiments.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Phase 3: Designing Value Propositions

Unit 2: Creating Studio Propositions

Aligning the concepts with the client's strategy

In this unit:

The aim was to test the value of the concepts, so the lab team could begin to assess which services could be engaging. At this stage, overall impact or efficacy of the proposals could not be verified, but it was possible to gauge desirability for users.

For the lab team, this involved bringing the concepts back from a more futuristic setting to a believable present scope, so that users were able to interact with the prototypes and the team could understand the value of each concept.

In parallel, the selected Studio teams (students) took their projects further, developing prototypes and testing them with users.

Another aim was to spark conversations with people around each topic, in order to collect deeper insights. These insights expand the understanding and perspective of both the organisation and the lab team. Ultimately, the approach puts the client in a position where they can answer questions like, ‘Is this service in line with our overall strategy?’ and ‘Should this service be built?’.

Overview

The process of turning the lab explorations into propositions required multiple stages. The main challenge was to transform those concepts —that had been created to fit into a particular future context— into propositions that felt believable and tangible today, while still investigating the critical assumptions related to each future scenario or concept.

The lab team had to shift from exploring possible futures to creating more plausible present concepts to be able to prototype and test their critical assumptions with users.

The explorations of service visions were not suitable for testing for desirability because the discussion would have likely been overtaken by the provocative and controversial elements of the ideas. However, the intended objective was to collect insight on how those concepts could impact people’s lives, if adopted. Should a natural path to these futures occur, the concepts may not seem provocative and therefore this influence had to be dulled.

The intent of the propositions was to be vehicles to explore more strategic questions with the users and the public. This meant they had to be convincing and easy to engage with in a meaningful way.

The approach the lab team followed to bring those future concepts into the present, is called ‘Backcasting’, a popular methodology used in the context of scenario planning. It is adopted by businesses and organisations that create future scenarios in order to outline the strategies they should adopt in the present to make those outcomes possible.

For the lab team, backcasting simply meant bringing their ideas from the future back toward the present —reframing the service visions as propositions that might exist in the near future rather than the far future. These reframed versions still retained a traceable line of evolution to the future, and they were therefore simply disguised and digestible, intermediary stepping stones.

With the new value propositions, the lab team then built prototypes to be tested with different types of audiences, such as recruited users, targeted users on social media and the client’s core team.

The result of testing with multiple stakeholders allowed the lab team to get quantitative and qualitative data, as well as strategic feedback to compare the concepts and conduct a final evaluation and selection of the propositions to prioritise.

Defining a design research strategy

The lab team went through a process of turning the explorations into propositions before prototyping and testing the concepts. Although the explorations were useful to extract insights on the themes and topics, now the lab team needed something more tangible, that people could relate to and believe.

To achieve that, the lab team followed a series of activities that helped them reframe the value propositions and prepare a prototyping plan.

This stage is called ‘Design research strategy’, meaning they went through a design process to reframe the value propositions, create a strategy to conduct research, outline a plan to test critical assumptions, gauge the desirability of the new propositions, and make the strategic alignment with the client.

To reframe the value propositions, the lab team followed a methodology called backcasting, which helped them transform the explorations into the more believable propositions. This process is also tied to the prototyping plan, as the propositions had been reframed in a way that made it possible to be quickly and easily prototyped and tested.

Activities

Activity 01.

Strategic Questions

The first activity was to review the assumptions linked to the explorations to understand which were safe assumptions and which required testing to be validated, i.e. which were ‘critical assumptions’.

For each of the selected explorations, the lab team went back to the original design challenges and scenarios and identified the initial key assumptions that led to the creation of the explorations. They then considered the original project goals and what the client wanted to explore based on their strategy. Then, based on all this information, they created a specific strategic question for each proposition.

These strategic questions helped the lab to maintain the right direction during the development of the prototypes, as well as further challenge their thinking. Each strategic question was a synthesis of the hypotheses made about the user, the problem and the solution’s mechanisms, combined with the client’s specific strategic interests in each area.

Activity 02.

Options for prototyping

After the definition of the strategic questions, it was necessary to start thinking about how to prototype and test the critical assumptions.

The objective was to structure the hypotheses into something actionable, which could be tested and validated. So, the team explored different ways of prototyping and tried to get an initial understanding e of the feasibility and timeframe to build the prototypes. To brainstorm those prototyping options, the lab team imagined how the concepts created for the explorations would look like in the present context, while maintaining the focus of the strategic question.

Thinking about ways to prototype at this stage made it easier for the lab team to narrow down the scope for the definition of the new value propositions, by considering what could be developed with limited time and resources

Activity 03.

Backcasting of value propositions

For users to engage with the concepts meaningfully, the lab team needed to reframe them to make them less provocative and less future-oriented, so they would interact with and critique the concept without spending time questioning the plausibility of the idea and instead to reflect on its impact

The way they did this was by following a methodology called ‘backcasting’, which is a practical approach that starts from the definition of desirable and optimal future scenarios and then works backwards to identify the main steps or mechanisms that can be applicable in the present to realise that future scenario. It is more common to see backcasting applied in the context of sustainability strategy; however, the lab team saw the opportunity to adapt the methodology to the reframing of the explorations in what they called ‘value propositions’.

For each selected exploration, the lab team had a strategic question and a series of critical assumptions. These were used as the starting point for the ‘backcasting’ process. While the importance of ethical exploration had always been present, this was a key moment to delve into it because the concepts were about to be taken to a more tangible level, and put in front of real users. It was the moment to examine more closely the these concepts’ impact on people and how the approaches aligned with the ethical principles of the client.

Considering all these elements, the lab team used the backcasting methodology to work backwards. From the exploration, which was an extreme idea set in the future, they started imagining how the users could genuinely adopt it. They started analysing how the mechanism they identified in the strategic question could be enabled through a service, how this service would look like if it existed today, what types of features it would have and whether the service could evolve into a future service that contained the critical elements of interest.

The resulting value propositions were not all entirely ethically sound. However, problematic value propositions and the responses they may elicit, still enrich our understanding of the plausibility of potential futures and inform current strategy.

The desirable future scenarios were those where a particular service provides users with more agency over their choices and an improvement to their health and happiness. The way the lab team framed each value proposition was to consider those scenarios as the outcome and then design propositions that could lead there, so they could understand if users also saw those scenarios as desirable.

In this way, each value proposition was simply a disguised and digestible, intermediary stepping stone into the future – these experiments allowed us to understand if users would engage with that first intermediary step, which tells us something about the potential of subsequent steps.

Activity 04.

Planning of experiments

With the value propositions defined, the lab team started outlining a plan to prototype and test them with the users.

As mentioned earlier, the objectives of testing of the propositions were to:

- validate the critical assumptions;

- measure desirability; and,

- evaluate the strategic alignment with the client.

For the lab team, it was essential to make the testing results comparable, so that they could make comparisons between the propositions and make an informed decision on which ones to bring forward.

Thus, they included three critical components in the planning:

- the research questions that needed to be answered through the testing;

- the methods that they will use to conduct the testing; and,

- the type of audiences they would test with.

The research questions were based on the critical assumptions, and they were related to the user, the problem and the solution. In particular, the lab team wanted to understand if the needs and goals they identified for the user segments were accurate, if the problem they defined was the right one to be solved, and if their proposed solution would be desirable to the user segment.

To find the answers to these questions, the lab team decided to collect qualitative data and feedback about the user, the problem and the solution, by speaking directly to the users. They used an external agency to recruit people who fit in the specific user segment of each proposition to participate in interviews and workshops. This segment was defined based on the identity of the extreme user profile of the first phase.

For each prototype, the lab defined what type of people they were looking for and created detailed briefs for the agency. The agency then used a ‘screening criteria’ for the participants’ selection, based on the information shared by the lab team.

As each user segment and the proposition were so different from each other, the lab had to ‘standardise’ the ways users would engage with the concept, through the creation of interfaces as prototypes, and using the same structure for all the interviews and workshops.

To test desirability, it was also necessary to think on a bigger scale. Therefore, the team used advertising on social media to present the propositions to the general public. They defined a strategy, which started by researching the best practices for the different platforms, identifying what channels and what type of media to use, and all technical aspects.

Finally, to test the strategic alignment with the client, the lab team proposed an in depth ‘Service Safari’ as a method to present all the concepts together with the insights collected from user testing.

Running experiments

The objective of the experiment stage was to explore the validity of the core assumptions associated with each proposition. The lab team designed this process as an experiment, creating low-resolution prototypes to test key assumptions and hypotheses, such as desirability and strategic alignment, and to answer the critical research questions. With only a minimum investment of resources, these steps inform the selection of concepts to bring to the next level.

This practice made an important contribution in de-risking the development of the services in the next stages, by putting the concepts in front of people and getting feedback early on, before significant investments of money and time were made. The three primary audiences for experimentation were: recruited users, who engaged with the prototypes directly; the general public, who interacted with the social media ads; and finally the client, who tested the prototypes and reviewed the insights to give a more strategic assessment.

The model was based on the build-measure-learn feedback loop, from the lean startup methodology. It is a loop constructed to maximise learnings by using an incremental and iterative approach.

It starts by turning ideas into something concrete and tangible;

then measures how people respond to them;

followed by a learning moment to process insights and make decisions about how to start the building stage again with new objectives.

What is interesting about the prototyping and testing of these propositions is how the future contexts were presented to the audiences. The new value propositions were reframed to be believable in the near future, but they still included some aspects of the far future scenarios. To the recruited users, the lab team presented the concepts as ideas that were in development. Therefore, they knew they were entering a research context, but reacted to the propositions as though they were a close reality, rather than hypothetical. With the advertising on social media, these fictional services were brought to an even more realistic level, by claiming they were in beta testing and about to be released in the market.

The use of these techniques to immerse people in a context where the propositions could conceivably exist, helped the lab team to validate the assumptions and get insights on the desirability of the concepts.

Activities

Activity 1:

Building prototypes

By rapidly testing multiple propositions, the lab team could assess the value of the concepts before investing significant time and resources into developing a smaller selection. The model had to create prototype results that could be comparable with each other and be flexible enough to allow quick and frequent iterations in order to tailor the testing with for different audiences

To test the propositions with recruited users and the general public on social media – the lab team developed some tangible artefacts to facilitate the interaction.

Starting from the core value proposition, they defined the main features of each concept in a way that would expose the critical assumptions. They then created a specific brand identity to convey the idea, its context, and who it was for. Then using these elements, the lab team proceeded to design the interactions and touchpoints, mostly by designing app mockups and clickable UIs (user interfaces) for each concept.

The features and interactions were summarised in a website landing page which was to be used as the destination for the adverts. And for the adverts, the lab team also prepared a series of images and copy. These included variations on the target audience and features in order to test multiple elements at the same time. All of these artefacts posed the proposition as a reality.

Activity 02:

Discussion of implications

After creating the prototypes, the next activity was to show those prototypes to people in the field to collect feedback and observe reactions. In this first round, the lab team worked with two types of audiences: recruited users and the general public on social media.

The lab team recruited a group of users for each proposition with whom they either conducted a workshop or individual face-to-face interviews. Face-to-face interviews were sometimes more appropriate due to the sensitivity of the topic. For other propositions, the lab team wanted to observe how participants would respond to each other and what conversations would be sparked by the interaction, so they opted for a workshop.

For both the workshops and the face-to-face interviews, the lab tried to standardise the structure by using the same 3-stage process:

- understand the users;

- understand their view on the topic; and,

- understand their response to the proposition as a solution to the problem

There was also an extra stage for filling in a standard scoresheet, which collected some quantitative data about the appeal, the impact, the influence on happiness, the significance, longevity, likeliness and trust associated with each proposition.

The lab team presented the context to the recruited users by introducing them to the central topic of health and happiness. They explained how the lab was conducting the research and that the objective was to understand how the users would feel about the service propositions. To limit any discussion about the legitimacy of the idea, the participants were told those concepts were in development and would potentially be released into the market soon.

In parallel to this recruited user testing, the lab team also conducted testing through advertising on social media. The objective of these ad campaigns was to generate comparative data on the performance of each different advert to understand which concepts were more desirable. Therefore, each concept has a standard advert structure and received the same funds. At the same time, they ran experiments with different audiences and highlighted different aspects of the service in order to test their research questions, the relevance of the problem, if their user hypothesis was correct, and the appeal of specific features —all simply by comparing the results of alternative adverts.

For each proposition, they had an image and text introducing the service, a call-to-action to find out more on the website – Then, on the website landing page, the users were prompted to leave their email addresses to get early access. The collection of emails was useful as quantitative data, but also to get permission from interested users to be contacted again.

Activity 03.

Synthesis of insights and discussion of learnings

At the end of this first round of testing, the lab team assembled the qualitative and quantitative data and feedback. From the recruited user interviews and workshops, they collected a series of comments and questions that they synthesised into insights. The insights were either about the user, about the problem or about the solution (following the same three categories used in the experiment).

For the more complex social media data, the lab team examined and compared metrics across all the propositions. They collected quantitative data from the performance of the ads and insights about demographics as well as some qualitative feedback through the users’ comments under the adverts. By analysing all the insights and data collected, they were able to validate or invalidate some of their critical assumptions and answer key research questions. This moment of synthesis was an advantageous point to make a strategic decision for each proposition, before entering the next prototyping round.

In the lean startup methodology, the options for this decision moment are called persevere, pivot or kill. For some of the propositions that reported quite successful results, the decision was to persevere, meaning they would enter the second round of testing without major changes in strategy. For others, the decision was instead to pivot, which for the lab team meant considering variations of the concept or hypotheses for further testing, such as a change in target audience or brand positioning, or even combining two propositions. This allowed them to explore and test other possibilities instead of killing the idea entirely because of less successful results. Only a few concepts were “killed” after a team assessment that determined they were not worth being brought forward, especially if they had not been as convincing from the start.

Active 04.

Refinement of prototypes

Based on the learnings of the first round of testing, the lab team assessed each proposition to see if there was a need for further testing with users. They took the insights and turned some into new research questions to test. The additional user testing was conducted through adverts on social media, which proved to be a quick iterative method to test alternatives. Some poor-performing propositions were excluded from this round. In contrast, for others, the lab team proposed different branding to test the appeal to different genders, or combined similar concepts to see if the proposition had stronger results. For these alternatives, they created new prototypes, such as interfaces and ads, and they modified the landing pages when necessary, which enabled them to experiment online with the public and collect fresh quantitative data.

Activity 05.

Second round of experiments

The second round of experiments included further testing with users and with the client to assess the strategic value of the propositions.They prototyped and tested some alternatives of the propositions using social media advertising, as they had done in the previous round of experiments by varying branding, features and positioning and then comparing success metrics to answer their questions. They tested only a few concepts, leaving out the ones that had great performance (and were already successful) and those that had poor performance in the first round. This process was intended to decide on ambiguous concepts.

The second type of testing in this second experimentation round was with the client. The lab team prepared for a workshop to present all the propositions and their main insights to allow the client’s team to become familiar with the concepts and discuss how strategically aligned they were with the organisation’s strategy and current objectives.

The type of workshop they conducted with the client is called a Service Safari, which allows the participants to take the point of view of the users by experiencing the services in first-person and by imagining the contexts in which those services would be used. For this, the lab team created a template to present all the elements of each proposition, such as links to UI prototypes, descriptions, features and insights.that In this way, the client’s team would have an instant overview of the entire service as well as information about the original problem and the strategic question.

The workshop had two parts associated with two objectives:

- To share with the client the progress made on the development of the ten selected concepts; and,

- to discuss the concepts together to better understand which propositions were more strategically valuable and to vote on which were priorities.

Each member of the client’s core team was asked to express a preference on the propositions by prioritising them using a scale from 1 to 10 and justifying their choices.

Activity 06.

Synthesis and conclusion

The lab team then reviewed the results internally, collecting and analysing all the insights from both experimentation stages and compared the data. The intent was to make sense of the qualitative and quantitative data and the strategic insights they got from the different audiences they had tested with, and therefore identify the potential opportunities for each proposition. They also internally reviewed everything they did during the prototyping stage, assessing what they did wrong and what could be improved, as well as the effectiveness of the testing methods they used.

Assessing and prioritising

The final assessment was conducted based on two main factors:

desirability, which the lab team evaluated mainly through the ads on social media; and,

strategic value, which they gauged from the interviews and workshops with recruited users and the workshop with the client.

This was to ensure that the subsequent development of the research would be about topics of relevance to the future because people are interested in them, and at the same time, bring new information that would be of strategic importance to the client’s future.

Activities

Activity 01.

Definition of metrics and KPIs

An essential activity for the assessment was the definition of the critical metrics and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) to consider for the next development phase. During the review of the concepts, the client identified some parallels between the lab team’s propositions and the research done by their emotional AI team and they saw potential opportunities to support each other’s work. On the client’s suggestion, the lab team organised a workshop to engage with the AI department, to understand more of what type of data they were collecting, what kinds of technologies they had available and how they measured success.

This was an excellent opportunity to align with the client not only on a strategic level but also regarding their technological prospects, so that they could potentially offer even more value to the client with the project. It was a way to explore ways to pivot some of the concepts to maximise value for all the stakeholders.

This session gave the lab team some direction in terms of which metrics to prioritise and how to measure the success of the subsequent developments.

By working with the AI team in particular, they defined priority metrics and targets for three main variables:

- user engagement

- data collection

- technology.

This model was an adaptation of the desirability, viability and feasibility lenses from the design thinking approach to innovation. For engagement, they defined a specific metric to measure success; for the data collection, they looked at how to generate the type of data they needed to train the algorithms; and finally, they brainstormed ways to test the potential of the technology.

Activity 02.

Comparison of results

The second activity of the assessment was the comparison of the results from the two experimentation rounds. The lab team had already compared the results of each proposition individually, but now it was about considering the propositions against each other in terms of desirability and strategic value.

The first set of data they examined was from the results of the social media ads testing to compare desirability. Among the metrics the lab team had tracked and measured during the experiment, the most relevant was the rate of sign-ups per landing page views. This rate measured the number of people who left their email on the landing page to receive early access, divided by the number of people who got to the landing page from the ads. They primarily used this metric to rank the proposition’s desirability (while still observing other results).

For the other key variable, strategic value, the lab team relied mainly on the prioritisation voting they had conducted with the client’s core team in the workshop. This voting had considered not just the importance of the concept itself, but also how relevant the entire topic was to the client. They visualised the two rankings with tables and identified which concepts resulted in being both desirable and strategically valuable.

Activity 03.

Strategic assessment

Once the lab team had identified the four most desirable and strategically valuable propositions, they conducted a strategic assessment to decide which concepts to prioritise for development.

They identified what outstanding questions remained unanswered from the prototyping and they outlined a strategy for further testing. They then met with the client once again and discussed the next steps. The ambition was to identify which proposition’s development to prioritise in the next stage. The questions discussed with the client to support the selection were – What could fit with their current strategy and offer credible but innovative alternatives that challenge the market and the organisation? What could be the most engaging value proposition based on pursuing happiness? What could help them explore use cases for ‘explainable’ and ‘emotional’ AI? And, finally, what could help them test the front-facing value of the concepts, their assets and their ethical standpoints.

The final decision was to prioritise a concept called EQLS, which aimed to help people with anxiety through the use of artificial intelligence. The plan was to develop more sophisticated MVPs to test other elements such as feasibility, viability, engagement and impact.

Case Studies

Propositions

Edit

Edit is a lifestyle service that helps you edit things in and out of your life through enriched tracking and mini-experiments.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Phase 3: Designing Value Propositions

Unit 2: Creating Studio Propositions

Aligning the concepts with the client's strategy

An overview of our design approach

The lab created tangible service visions (i.e. future concepts) to help the client expand their collective imagination of plausible future services and discuss the potential opportunities and implications these future services could bring to our society and the organisation.

This phase concentrates on turning those potential services into concrete experiences. In this way, the users experience the services, while allowing the lab to experiment. In order to manifest this degree of realism, the lab created propositions that take multiple forms.

This process allows the lab and the client to assess the desirability of the concepts, as well as address the strategic questions connected to each concept in order to prioritise them for the following stage.

The theory

The lab formed three main hypotheses of customer development for each of the future concepts developed in the previous stage:

- a user hypothesis (Was the user segment relevant for the strategy?);

- a problem hypothesis (Was the problem identified in the segment worth addressing?); and,

- a value hypothesis (Was the service approach interesting as a mechanism for tackling the problem?)

Then, using a set of practises inspired by the practical principles of Eric Ries’ Lean Startup, the Lab converted each future concept (which at this point were simply futuristic ideas) into concrete experiences that could make the fictional, future service accessible to people in today’s world.

The lab created these experiences or experiments to collect quantitative and qualitative data about how customers would respond to a service, should it manifest. It also enabled them to test each hypothesis. This innovation process is called hypothesis-driven design, which consists of generating hypotheses or assumptions and then testing and validating them, in order to create potential solutions.

This process helped the lab focus and test their assumptions and helped the client assess the strategic benefit of each value proposition, minimising the required investment and reducing the risk of pursuing a service nobody wanted.

Importantly, this process also allowed the client to engage in conversations about the ethical implications of such services proliferating. This conversation space was a novel environment for the client, facilitated solely by the lab’s work to manifest these fictional services.

We refer to these concrete, fictional experiences as ‘Value propositions’.

The process

This third phase had a different process for the lab and the studio, even though in both cases the objectives were to test the desirability of the concepts and their strategic alignment with the client.

For the lab, the main challenge was to compare the concepts and make an assessment on which ones to take forward. For the studio, each team focused on one concept, so there was no selection process involved. Instead, they started to evolve the proof of concept through rounds of prototyping and testing.

For both the lab and the studio, the priority in this phase was to test the critical assumptions associated with the explorations. In particular, they needed to test three things —who the users were (the user-hypothesis), whether they had the specific problem (the problem hypothesis) and whether they truly needed and desired what the concept was proposing (the value hypothesis).

The way the explorations had been framed in the previous phase was not compatible with the type of testing required for this stage. The explorations had been created based on specific future contexts, which meant present day people would largely question the legitimacy of the idea and it would be difficult to get meaningful feedback. Therefore, the work done by the lab team in this phase started with the reframing of the explorations into more believable and relatable representations, called value propositions.

The value propositions needed to be quick, cheap and easy to prototype, so they could quickly be used to gauge user interest and reactions. The idea was to get as many learnings as possible from the testing phase and to be able to refine and iterate rapidly.

The outcome of designing and testing the propositions was a collection of data, feedback and insight on all the concepts. For both the lab team and the studio, it was crucial to know that the directions and decisions they were about to make were based on evidence and validated assumptions, before getting to the actual development of the Minimum Viable Products (MVP’s).

In the end, the goal for the lab team was to be able to make a selection of concepts worthy of more investment (time and money) for the next development phase. For the studio propositions, the focus was on proving the concept and defining a strategy to take the projects forward.

Design Value Propositions

Explore how the lab created tangible service visions (i.e. future concepts) to help the client expand their collective imagination of plausible future services.

Unit 1: Creating Lab Propositions

Case Studies

Propositions

Edit

Edit is a lifestyle service that helps you edit things in and out of your life through enriched tracking and mini-experiments.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Edit is a lifestyle service that helps you edit things in and out of your life through enriched tracking and mini-experiments.

What’s the problem?

While there are seemingly endless resources, research, and tools for building healthier habits, people continue to struggle with a sustained change in behaviour over time. When it comes to health and wellbeing, people tend to struggle with four main areas: control, accountability, personalisation, and reward.

Control:

People usually begin a journey to change behaviour with a fundamental misunderstanding about what it takes to accomplish such a thing. Many of our behaviours are deep-seated and are significantly more challenging to change than perceived. This inevitably leads to what we refer to as a relapse and a feeling of helplessness. To be more specific, people feel that they lack control because they lack awareness and context for their behaviour.

Accountability:

Ultimately, most people accomplish things that they feel accountable for achieving. When it comes to most wellbeing goals, most people don’t have a high enough accountability level to change behaviour in a sustainable way.

Personalisation:

While there are many approaches to creating a new habit, unfortunately, many are generic and don’t consider human beings’ nuances. Things like personality, culture, and life experience make up who we are and how we behave, which is why individuals need a personalised approach to behaviour change.

Reward:

Reward, recognition, and incentives all play an essential role in long-term behaviour change, but all too often, those things come in a delayed manner. The lack of immediate reward causes many people to relapse towards old behaviours much sooner without the motivation to make a new attempt.

The four areas briefly described above came from research conducted with people trying to change addictive behaviour. Specifically, we worked with people trying to quit smoking to understand behaviour change on a more intense level. As one of our research participants said, “I am a single mother of 4, working in the male-dominated world of finance, and the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life was quitting smoking.” While we also worked with leading researchers and experts in behaviour change, it ultimately was the work with these “extreme” users that provided the most insight into Edit’s development.

How ‘Edit’ responds

Edit responds to the above challenges by breaking the traditional behaviour change cycle and forming a new continuous cycle that focuses on action and learning, rather than relapse. We designed Edit as a modular service that provides people with options for engaging in a continuous cycle of action and learning to build healthier habits over time.

Chat, Story, People, Explore:

Edit consists of four main service components: chat, story, people, and explore. Certainly, we believe that the service is most potent when engaging with some combination of all four service components, but Edit also accommodates the person interested in some. These components are driven by enriched tracking that uses multiple sources of data to help users better understand the impact of their daily actions on their well-being.

Chat:

Through the Edit Bot, users can provide context to their actions during the day, ask questions to help customise edits, and receive quick updates on progress.

Story:

Through a feed of insights and accomplishments, users can socially share progress and choose new edits to try based on newly developed insights.

People:

By connecting with people in the Edit Community, users can learn from others who are going through similar journeys—inspiring them to try different edits.

Explore

Through a marketplace of organisations (example: NHS) and individuals, Edit users can discover new edits to try, sell (or gift) their own edits, and begin other behaviour change journeys with confidence.

To illustrate how these features can work together, it is useful to look at them in the context of one person’s journey using the service.

What we

learnt

Although most people are continually thinking about how they can be healthier, they require a drastic event (medical reasons, family reasons, or intense life experiences) to trigger an actual change in long-term behaviour. Through this project, we’ve found that there are some less severe ways that more people can build healthier habits. By understanding the impact of daily actions and creating new and personalised rituals (edits), people are able to build enough resiliency to not only survive a relapse in behaviour, but turn it into a meaningful moment of learning. That is the key to consciously building healthy habits that will increase one’s overall wellbeing.

The Value of Behaviour Change

While we discovered the power of enriched tracking and small daily edits in changing behaviour, it is also clear that behaviour change has a variety of value. Of course, it has value to the individual and those people directly in their lives. However, and more interestingly, it has value to society as a whole. Edit ultimately attempts to solve the challenge: how might we connect a person’s actions with an immediate and individualised reward with a more significant impact on society’s overall wellbeing?

By moving habit formation away from generic models to giving people full agency over their wellbeing, as they define it, we can create a massive and highly intelligent database that understands behaviour change on an incredibly granular level at scale. What we do with that is the critical question. Suppose we can leverage this theoretical intelligent database appropriately. In that case, we could create communities centred on wellbeing, which may ultimately improve population health and reduce unnecessary stress on healthcare systems.

Our new direction of exploration

The entire premise of Edit is that people have an open and transparent relationship with the idea of behaviour change. Unfortunately, in our culture, a behaviour change is often seen as criticism, failure, or even an embarrassment. As trends around health and wellbeing continue to grow, we wonder how something like Edit could be positioned to shift the societal mindset towards behaviour change fundamentally.

Rhea Belani

Related to ‘Edit’

Scenarios

Personal control

Devices quantify and measure all aspects of the people’s lives and body amplifying obsessive behaviours. People’s personal identity becomes more based on an idealised virtual version of oneself rather than your existing reality.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

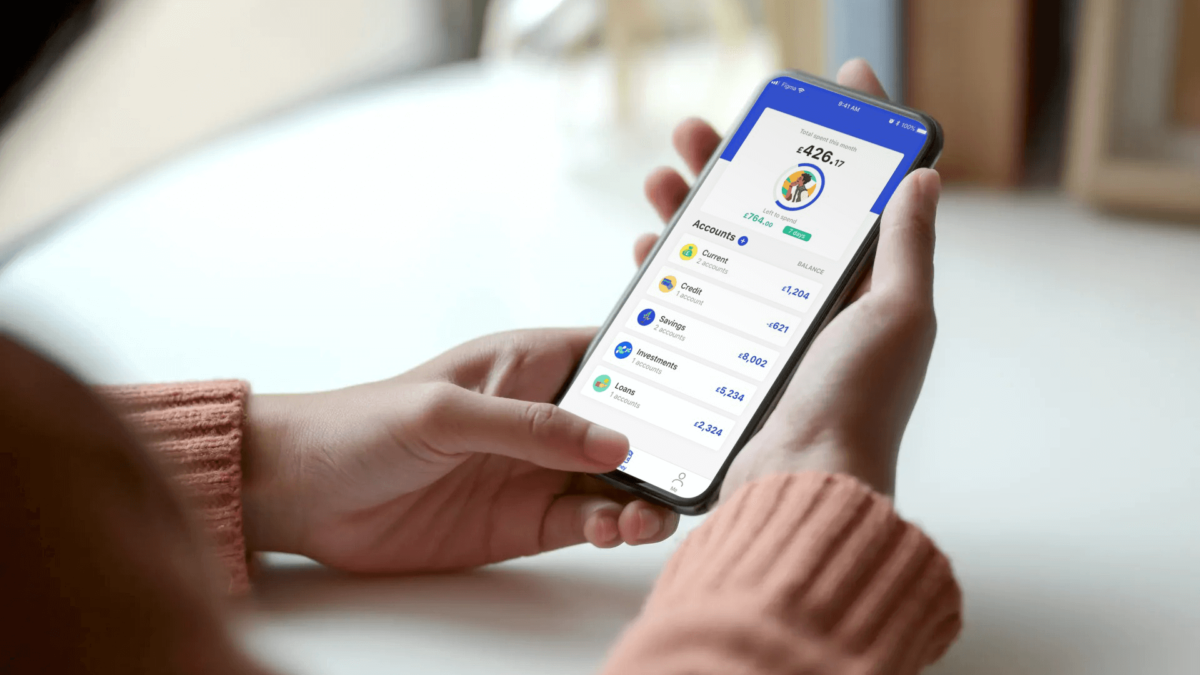

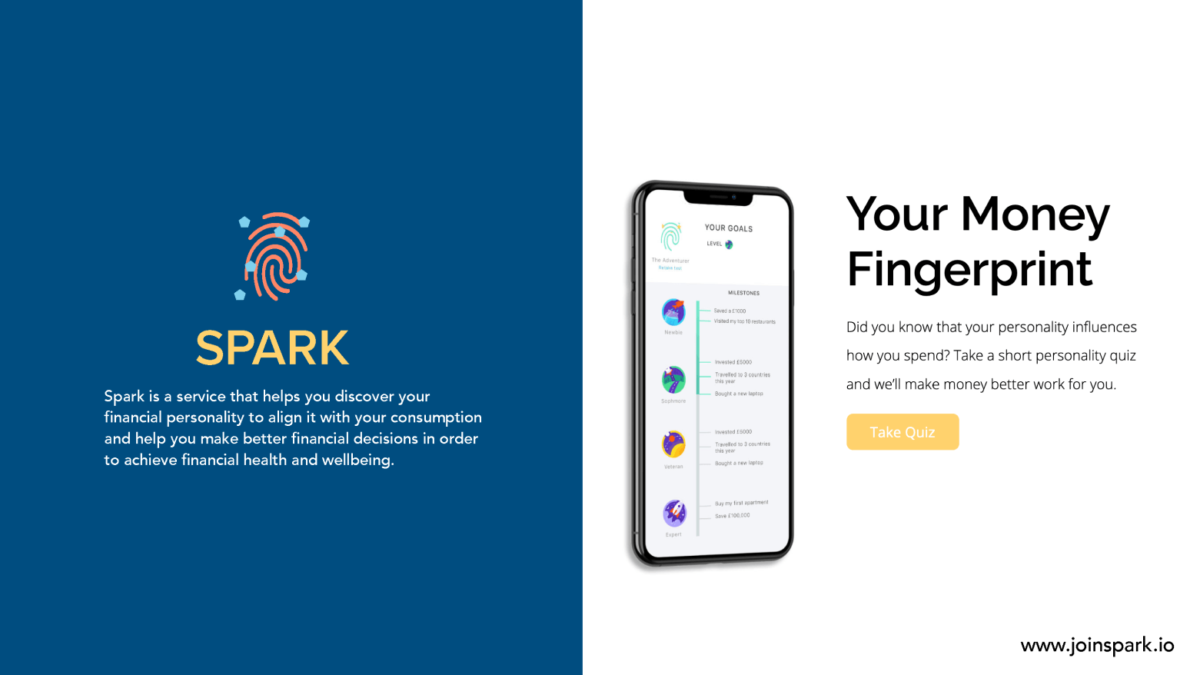

Spark is a service that helps you discover your financial personality to align it with your consumption. It helps you make better financial decisions and achieve financial health and wellbeing.

What is the problem?

We know that people do not always act rationally or in alignment with their intentions, which from a financial perspective often means that money is not used in the ways that bring people the most happiness. This could be because it is either spent too much at times when frugality would bring more happiness or because it is spent on things that are not the optimal way to exchange money for personal value.

Within this context, we can look to the world of financial institutions and argue that the services in place to serve people financially are set up to profit from people’s bad decisions rather than to help people achieve more wellbeing. For young people just graduating college and entering their first jobs, there is a sense of anxiety that they do not have the necessary control over their money and that the way they interact with services often feels like a ‘one-size-fits-all’.Ultimately, they feel the solutions provided don’t fit their lives. Moreover, people’s financial behaviour changes according to their personality, meaning that you will spend and save money in different ways, and that you will take happiness from how you’ve spent your money in different ways depending on your personality.

There is a mismatch between banking services’ blanket approach to supporting people financially and the reality of how people interact with and value money. It’s in this environment that young people are leaving education with low financial literacy, low savings and new financial responsibilities and expectations. This not only leads to anxiety around financial decision-making, but also to ineffective relationships with money that can perpetuate and have serious implications on people’s lives.

How ‘Spark’ responds

Spark responds to these issues by integrating the attributes of more personalised lifestyle services with typically rigid financial tools. This means that not only does the service understands its users and customises the advice it gives accordingly but it is able to tune the entire service right down to the financial dashboards. In this way, the objective of the service is to help align how someone uses their money with their personality type. In doing so, it builds clarity and a sense of control that can improve people’s long term financial health and wellbeing.

Personality Test:

When they start the service, the first thing people do is complete a quiz about their personality, which provides them with a match, showing them how people with their personality typically like to spend, save or invest. Money does not equal happiness, but when people spend their money according to their personality, it can lead to more happiness. This personality test is the first step to creating a bespoke service for each user.

Mirror:

Through open banking, people connect their different accounts so that Spark can analyse and then reflect back to people how they spend their money. These categorisations and visualisations can give a fresh perspective, which can help people understand where their money is going and how much they’re really saving. This alone may help people find a new level of control and illuminate opportunities for new habits that will make them happier.

Goals and Advice:

Spark combines its understanding of people’s personality and their spending behaviour with specific financial and life goals so that it can provide the most meaningful advice possible. It’s able to show people a path forward of what can be achieved if they take Spark’s financial advice.

Access:

Finally, Spark gives each user a financial health score based on their financial behaviour . This score is connected to how well they are progressing toward a goal or how much they are improving. A high score means a user has access to other Spark accredited financial services like a low cost loan or or a better credit card.

What we

learnt

We demonstrated a low fidelity prototype of Spark to our users and their response was very positive, generally demonstrating a high desirability and a promising area of opportunity for using these approaches to improve people’s control over their finances. The proposition also sheds light on some interesting questions that emerge as services move into these new spaces.

It’s clear that there is a relationship between people’s personalities and their financial habits. When this relationship is incorporated into services, it can offer people more control and potentially greater happiness for the same amounts of money. However, while tailoring financial services to people’s personalities might be good for some people, it’s not clear how vulnerable these systems may be to bias (against particular personalities) or what it means when a user shifts between genuinely changing their character or behaviour, playing the game just to do better, or simply cheating the system. Below we explore the overall topics.

Engagement

Through the research, we realised that there was a lot of connection between people’s anxiety and stress and their financial health, but that money management was seen as boring for the target users. The perception was that these financial considerations were something for later in life so the challenge in the service is about how to help people engage in a productive but seemingly ‘boring’ process.

Users found Spark to be valuable because it responded to this problem by making it fun and engaging. Firstly, by stating that there is financial gain to be had from using the service, then by using an engaging and illuminating quiz and finally, by making the service about almost everything else except money and visualising money in relatable terms like the number of activities they could do with it. It’s through these mechanisms that people were able to enjoy the concept. We found that even by simply visualising people’s money differently, behaviour could be changed, and this could ultimately lead to increased wellbeing.

Avoiding addictiveness

We found that there was some concern among users that a service like this could become too addictive. The gamified elements of the service make it fun, which in combination with the importance of money in people’s lives and how often they interact with it, it seems that it could become a fertile ground to cause addiction, which would ultimately have a negative impact on people’s anxiety levels. In response, Spark could attempt to recognise addictive behaviour and move certain activities into the background to prevent the user from over-interacting with the service in unhealthy ways.

Avoiding biases

An emerging issue within the spark concept is around how a service like this can base its offerings on someone’s personality in order to tailor the service, without also risking excluding people from financial services because they might have personality traits that are less ‘financially attractive’.

When considering access to credit, people can adapt how they look in the app and play the system to get the best financial opportunity. However, there is also a risk that people with less common personality traits may not get access to a financial opportunity because their profile is poorly understood and therefore represents a risk. How can financial services adjust to people’s personalities without essentially discriminating against people based on their personality?

Playing, Cheating or Changing

We also see an emerging issue regarding how people might adapt to financial gain. If we envisage a scenario where people are able to convince a service that their personality is more financially attractive, then there is a lot of evidence to suggest that people will do so. If we build on this scenario, proposing that in the future someone’s personality will be more intricately understood by the service through more sophisticated data and analysis —at what point does it become impossible for the user to game the service and to what extend would users adjust themselves and their lives and the appearance of their personality to be seen as more ‘financially attractive’? Could the overlapping of personality and finance, in more sophisticated ways, lead to the emergence of characteristics that cost people more money, essentially ‘expensive personality traits’?

The proposition is premised on the idea that by offering people information about their personality, their behaviour and the financial system, they can be more in control of their finances and their financial wellbeing. Users are essentially encouraged to play a game with their personality and their behaviour in order to improve their financial wellbeing. At what point does playing the game mean sacrificing too much for the sake of financial wellbeing ?

Jump to:

Service visions

Guru

Our new direction of exploration

If this proposition is progressed, the strategic question of relevance to our investigations is more along the lines of:

As the world of financial wellbeing overlaps with sophisticated personality assessment, how can we find a balance that encourages an appropriate level of gaming one’s life for financial wellbeing, without damaging people’s freedom to be who they want to be or discriminating against people based on their personalities?

Nafeesa Jafferjee

Related to ‘Edit’

Scenarios

Personal control

Devices quantify and measure all aspects of the people’s lives and body amplifying obsessive behaviours. People’s personal identity becomes more based on an idealised virtual version of oneself rather than your existing reality.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

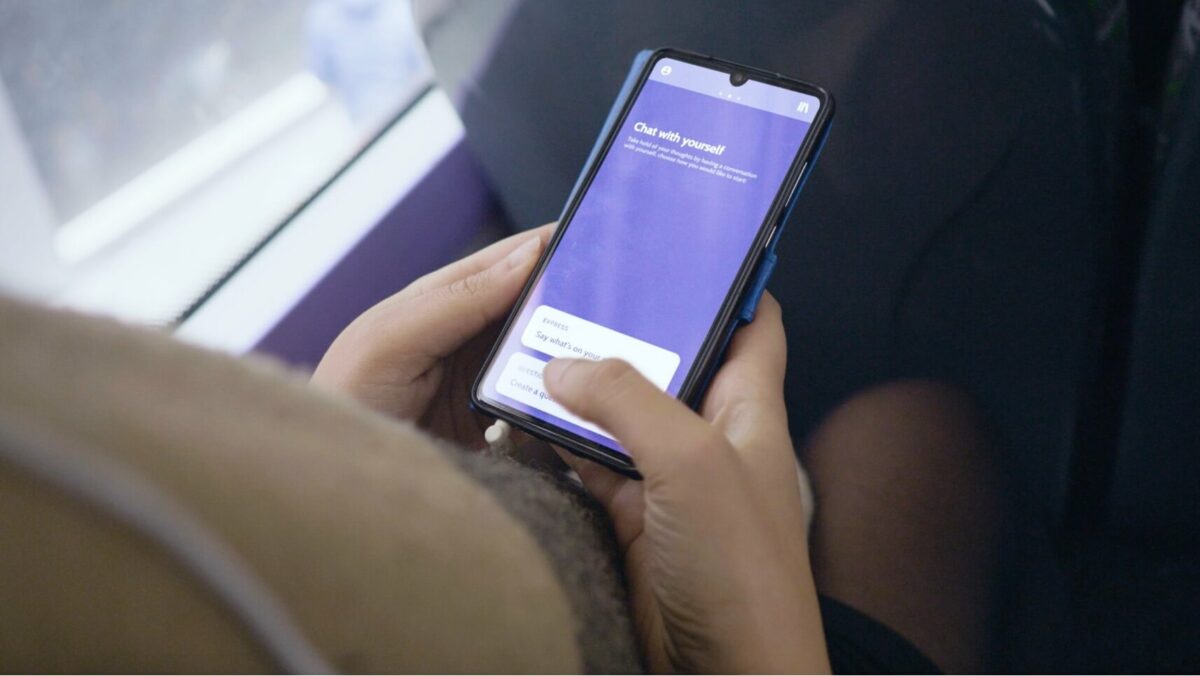

Mymes uses an understanding of people’s behaviour to create simulations of their future to help them make decisions .aIt distills different sides of their character to help them explore who they are.

What is the problem?

People sometimes struggle to make decisions that benefit their future and a lack of identity exploration can hinder people’s resilience.

The Mymes proposition responds to two overlapping problem areas. On the one hand, we see that people, particularly young people in significant transitionary moments of their lives, struggle to make complex decisions.

For instance,, we can see that lifestyle related decisions perhaps around food, stress, exercise, sleeping or smoking, drive a huge amount of the chronic health conditions faced in the United Kingdom On the surface, it’s possible to argue that the healthier options in these cases are simple to choose, i.e. ‘don’t smoke, eat healthily, sleep more’, but in reality people have to make complex assessments to do with money, work, finance or relationships,which can make these decisions difficult.

The other area of interest within this proposition is about the exploration of identity. Research suggests that when young people explore their identity i.e. they try out different models of identity, experimenting with how they can fit within the world and see themselves. They can often be more emotionally resilient later in life when something challenges the identity they had established. It is argued that as a consequence of having experimented with who they are, they become more capable of reforming their perceptions of themselves without the same level of emotional loss as somebody who had not experimented. Additionally, it could be argued that people have different identities during the same period. Someone may act, behave and feel completely different during different contexts even on the same day, therefore, it may not even be that people are experimenting with their identities one at a time. This proposition also considers how AI may be adopted to support people as they navigate the complexity of identity exploration.

How ‘Mymes’ responds

Mymes empowers users with high levels of personal data and insight. It uses this data to show people future versions of themselves, which are based on their choices in the present, enabling longer-term decision making. The service also helps people understand a nuanced, multi-faceted perspective of their identity, expanding people’s concept of themselves and encouraging self-exploration

Simulate the future:

Mymes creates a digital avatar of the user, simulating potential future outcomes of their decisions through AI. Initially, it would take in data from all of your other apps and support simple decisions, such as how to adjust your daily commute in ways that might save you money or uplift your mood or improve your health. But after a while,the service would start to develop its own intelligence about you and simulate more complex alterations to your life. It allows people to explore their potential future realities, helping them think about longer term implications and consider more options.

Monitor and track your life:

Mymes drives its simulations through the monitoring of any actions people allow it to monitor by connecting with other apps and devices. This data not only drives the simulations, but it also helps people understand their own patterns simply through giving them more visibility and transparency on their behaviours. Essentially, the service is trying to use the power of its data to help build a users’ agency through teaching them about themselves, and subsequently helping them make more informed decisions by themselves.

See different sides of yourself:

As Mymes learns more and more about people, it’s able to discern different modes of behaviour that happen at different times, in different cycles, in different places, at different events, under different conditions and with different people. It categorises these variations in people’s behaviour to form representations of different sides of them, so they can see the different modes of behaviour they adopt in different circumstances and with different people.

See how different versions of you behave:

These different categories can be explored by the user allowing them to see things such as their spending behaviour, the types of food they eat, and depending on the sensor data that Mymes is allowed to collect, it could even monitor some variations in emotional states. These different categories of self, could distinctly represent elements of people’s identity that are heightened in different contexts and help them discern a more varied and nuanced understanding of themselves, rather than trying to form a singular coherent concept. In doing so, Mymes creates paths to explore identity in new ways.

What we

learnt

We demonstrated a low fidelity prototype of Mymes to high-need users and this is what we learned:

- that many people appreciated that the problem Mymes was trying to tackle was real and that the general approach of the service was appropriate;

- most people were sceptical about how much they would use the service; and,

- there was a lot of disagreement among users about how the strategies could be refocused to improve it.

Emerging conversations from this proposition are about:

- the way that choices can be supported by technology without becoming invasive; and,

- how having multifaceted representations of oneself could practically be valuable in everyday life.

Only some choices should be supported

An interesting area of discussion that emerged with users was around what was an appropriate recommendation, or simulation to be given. The general approach of the service proposal was that it could be wide ranging and encompass large categories of your life, offering anything from health simulations to career simulations. The simulations were illustrated to give people a more engaging way to interact and understand the outcomes of their actions, but most users found these illustrations inappropriate for anything other than very practical choices.

There was wide disagreement among the group about how and when people wanted an intervention from the app. Some said that it could feel overbearing for the intervention to be regular. Some said that it would be best if it intervened regularly in small health choices that have larger long-term implications (like dietary choices for instance). Others felt that technological services like this could only help with decisions that are failed by absentmindedness, therefore the service could intervene to improve the decision.

This variety of opinion is evidence that services that become intertwined so intimately with people’s lives, either need to learn to be adept at responding to the users’ cues for assistance or they need to have active personalisation built in the service experience.

Categorising identity

People found the concept of categorising different aspects of themselves useful as a mental exercise. And for many of them, it helped them feel positive about themselves because, to them, it meant they had varied and complex characters. Many participants also talked about how the recollection of sides of themselves, which are now less active, was both nostalgic and powerful —because although that side of themselves was less active, they felt it still belonged to their identity and seeing or describing it enriched their current view of themselves.

Although most participants felt that categorising sides of themselves was meaningful and rewarding, they struggled to see how digital categorisation would be helpful in their lives beyond simply being a reminder or an archived part of themselves. The proposal essentially suggests that a divided conceptualisation of the self, might expand people’s self-understanding. And that reminding people of their potential to be multifaceted could encourage them to explore more. However, this relies on a large assumption that the categorisations would be sophisticated enough to be taken seriously and would inherently convey a message that, ‘people can be whoever they want to be’. To the participants engaging with the proposal, this was not a safe assumption and the feature was unappealing.

If we simply consider the fact people felt enriched and more powerful having recalled categories of their personality (without the strategy employed by Mymes), it is clear that it is a valuable component of people’s self-reflection, and therefore, perhaps there are still some interesting questions to be explored in this space with different concepts: Could reflecting on oneself through the lens of different personal identities help people feel more free to explore and act in ways outside of their current ‘preset character’? Could it help them understand themselves in more depth? Could it help people to act with more control?

Our new direction of exploration