Phase: Explorations

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

This tool helps you define the design challenge for the brief. Create one for each dimension of change.

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

This tool provides a detailed understanding of the client’s response to each service concept. Use this tool or a digital surveying tool. Once you have all the responses, you can compare quantitative results and discuss the selection.

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

This tool will help you tell the story of the experience of the user when they engage with the service, considering how the user starts with a problem and how they are influenced by the service.

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

The ‘Design Challenge Analysis’ tool is used to explore and discuss the value of each design challenge. Use one page for each dimension of challenges. Use the design challenge table to organise all the challenges and vote.

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

The design challenge table is used to organise all the challenges in order to facilitate conversation and voting. Use the ‘Design Challenge Analysis’ tool to make notes and use this tool to manage voting.

Design Challenge

Why is this tool useful?

The Future Wheel is a method for graphical visualisation of direct and indirect future consequences of a particular change or development. It was invented by Jerome C. Glenn in 1971, when he was a student at the Antioch Graduate School of Education (now Antioch University New England). The Future Wheel is a way to organise thinking and questioning about the future — a kind of structured brainstorming.

Phase 2: Explore service visions

Unit 2: Conducting Studio Explorations

Involving the RCA students

In this unit:

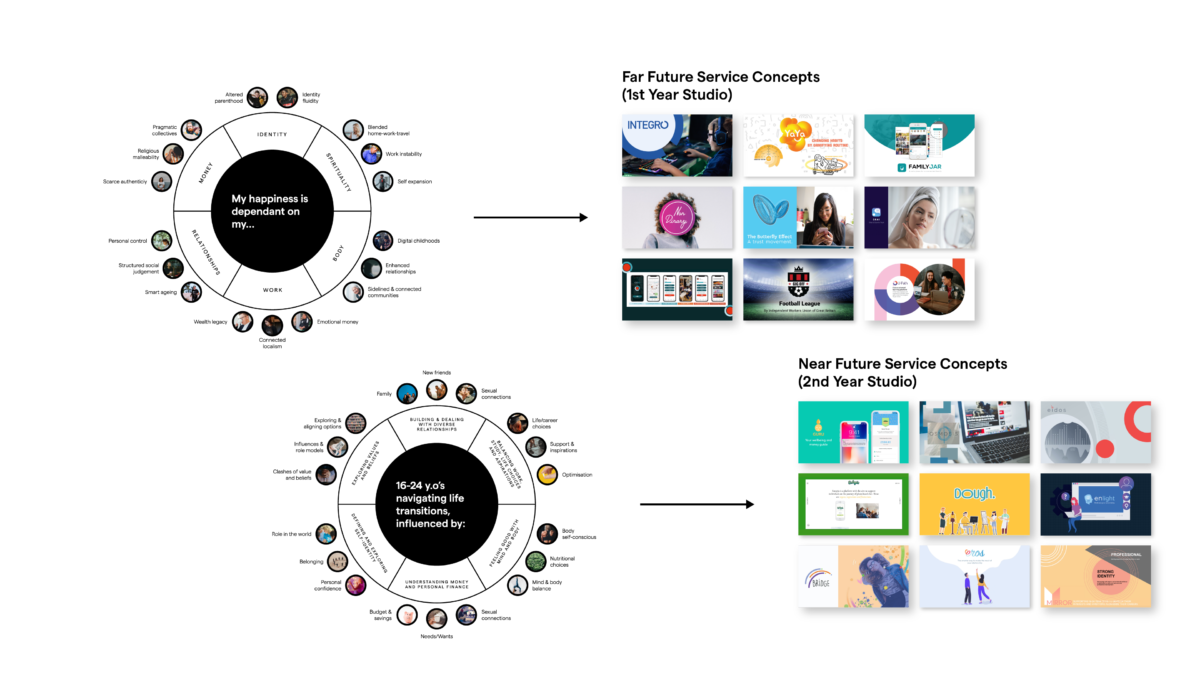

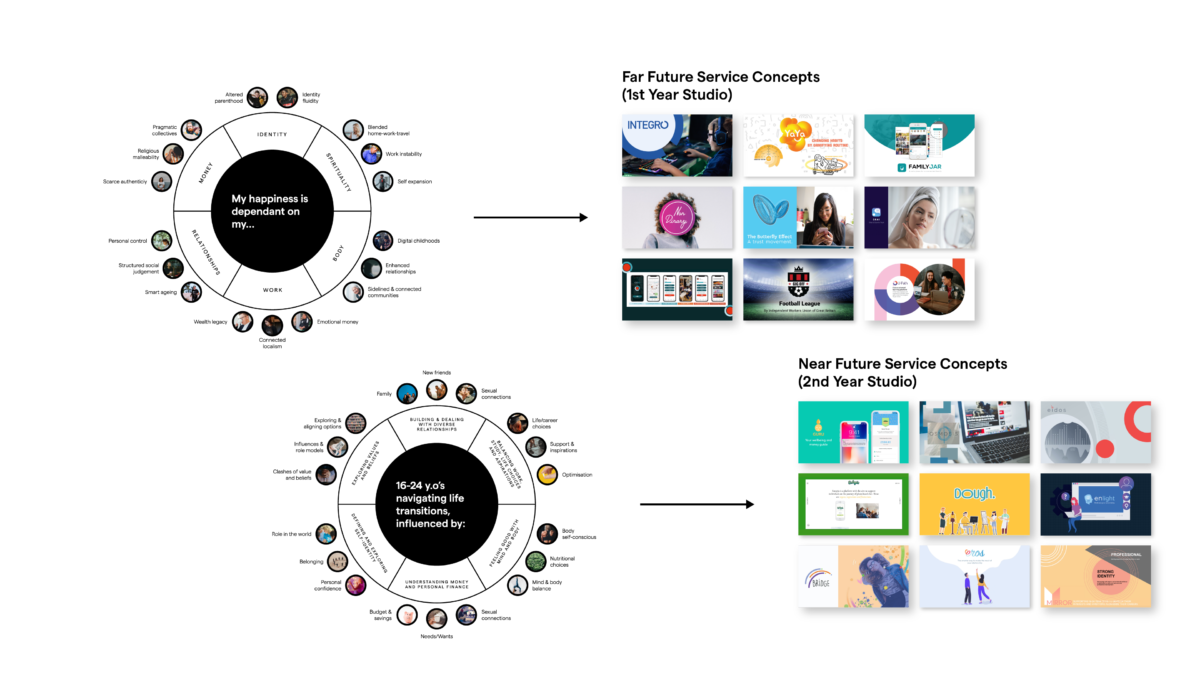

Like in the previous unit, the aim of this work was to create concepts that are diverse enough to scan the landscape and provoke conversation about the huge diversity of potential issues and opportunities in the future.

However, this unit harnessed the creativity and diversity of experience and culture of the RCA’s Service Design students by combining the service design methodologies from the course with the need to generate focused service concepts for the project.

Alongside the educational aims of the student projects, this unit also aims to harness the diverse thinking of student cohorts to expand the thinking of the lab team and the client.

Overview

*The term ‘studio explorations’ refers to the future service visions designed by the first and second year students of the MA Service Design course at the Royal College of Art.

Before the start of the collaboration between xploratory and the client, the Service Design programme had previously partnered with the company by setting briefs and working with the students of the course. As it had proven valuable for the client, the xploratory lab team planned to run parallel work streams with the students.

As the lab team had led their own explorations, they had enriched knowledge on the topics and themes for briefing the students. The approach they took for the studio briefs was different from their own, internal ones. They were aware it was not possible to have the students follow their same process to envision concepts, nor did they want that. There were different aspects to take into consideration:

First, the students had to follow the service design process in the development of their projects, as indicated in the project guide of the course.

Second, given the limited time they had to work on their projects, the lab team needed to focus the students’ efforts where it was most valuable. The second year students focused on a time horizon much closer to the present (the ‘Near Future’), and the first year students were tasked with expanding and enriching the prospects of the ‘Far Future’ time horizon.

Additionally, to make sure that the projects aligned with the client’s strategy from the beginning, in terms of goals and principles, the briefs combined the research done on the future trends and extreme users, with the research on the client’s strategy.

However, as the aim of the studio explorations was to help them expand the client’s thinking, the lab team did not want to put too many constraints on the students, so they kept the briefs fairly broad, and let the students give their own perspectives on the topic of the future of health and happiness.

Through tutorials, reviews and meetings with the students, the lab team supported the work of the studio and mediated between the students and the client. The students’ projects created meaningful value to the client, expanding and enriching the thinking and uncovering new perspectives of health and happiness.

Briefing the Studio

The lab team had different objectives set for the first-year and second-year students of the programme. They wanted them to tackle different types of challenges with varying levels of depth and breadth based on their knowledge and experience.

For the first-year students, the brief was their first project on the course, so they knew they would still need to become familiar with the service design tools and methodologies. Their brief was therefore more explorative.

The second year students were expected to be able to build on their briefs, identify the most relevant problems and design and prototype services to address those challenges. This is why they created two different brief strategies, with different scopes and objectives.

Activities

Activity 01.

Prioritising workshop

As mentioned in the previous unit, during the workshop for the refinement of design challenges, the client and lab team also discussed the prioritisation and allocation of topics for the student briefs. In particular, they defined a few selection criteria, which they used to review the themes and the challenges.

The lab team and the client initially arranged and adjusted design challenges into two categories.

- The ‘Near Future’: more immediately and strategically valuable for the client

- The ‘Far Future’: more unusual and provoking and needed more explorative work.

The practical work of creating service concepts for the lab team (explained in Unit 1) only focused on the ‘Far Future’ horizon, but would greatly benefit from the diverse perspectives of an entire year group of first year students. The second-year student brief aimed to create robust service visions, which could be deployed in the ‘Near Future’ horizon and match the client’s immediate strategy.

Activity 02.

Briefs write-up

With the prioritisation of topics that the lab team agreed during the workshop with the client, they were able to begin writing the briefs. The briefs began with an introduction to the client’s mission and their approach and strategy, followed by an overview of their primary area of focus: health, happiness and wellbeing.

The lab team then described the various potential contexts and problem areas. They also prepared a synthesis of the research they had conducted on health and happiness and explained the importance of people having agency over their health choices.

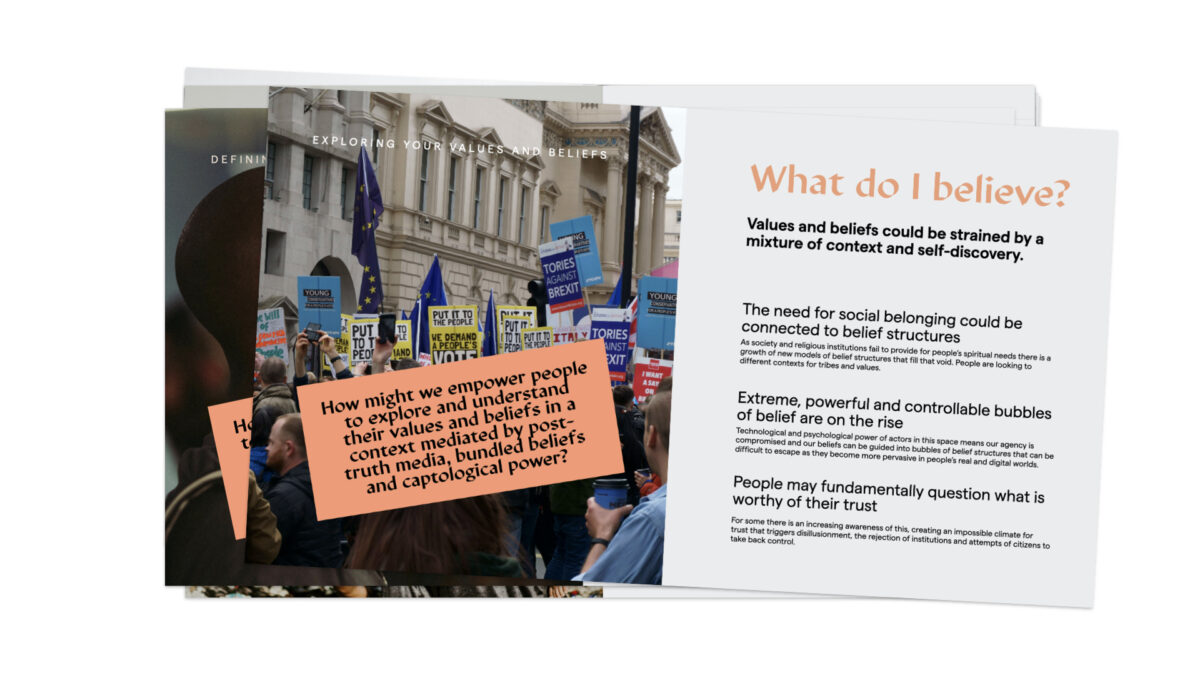

After, the lab team had to take two different approaches that distinguished the brief of the first-years from the second-years. For the first-years, they created a more explorative brief focused on the ‘Far Future’, using the societal dimensions as the starting point. And then for each one, proposed a particular problem area that the client and the lab team found relevant and interesting to delve into. They were expecting the students to help the lab team and enrich the client ‘s views with a diversity of cultural, ideological, social and disciplinary perspectives coming from any source of inspiration they might find relevant.

For the second-years, they created briefs that were aligned with the research done on the client’s platform, and more focused on the ‘Near Future’. As with the first-year’s brief, they started from the key themes. However, in this case using the persona developed for the scenarios of the ‘Near Future’ (see phase 1), they focused on a specific target user and encouraged them to explore what their needs and challenges would be.

The second-year students were expected to unpack problems and investigate how science, business, technology psychology, and design could be combined to create service visions able to address those challenges.

Activity 03.

Presentation of Briefs

The lab team presented the briefs to the students at the start of the year, before the creation of their teams. Each one of the cohorts was introduced to six different design challenges, one per societal dimension related to health and happiness. These challenges were much broader than the ones they had created for the lab challenges, as they encouraged the students to bring their own point of view.

Once the teams were set up, they asked the students to give a first thought on what approach they would like to take and what theme they wanted to focus on. This really helped them understand what the students were going to cover, and how they could complement their work on the lab explorations with the students’ work.

Crafting Service concepts

The students were provided with a project guide, which is a document the programme provides each term, with the main milestones and deliverables requested for each tutorial and review.

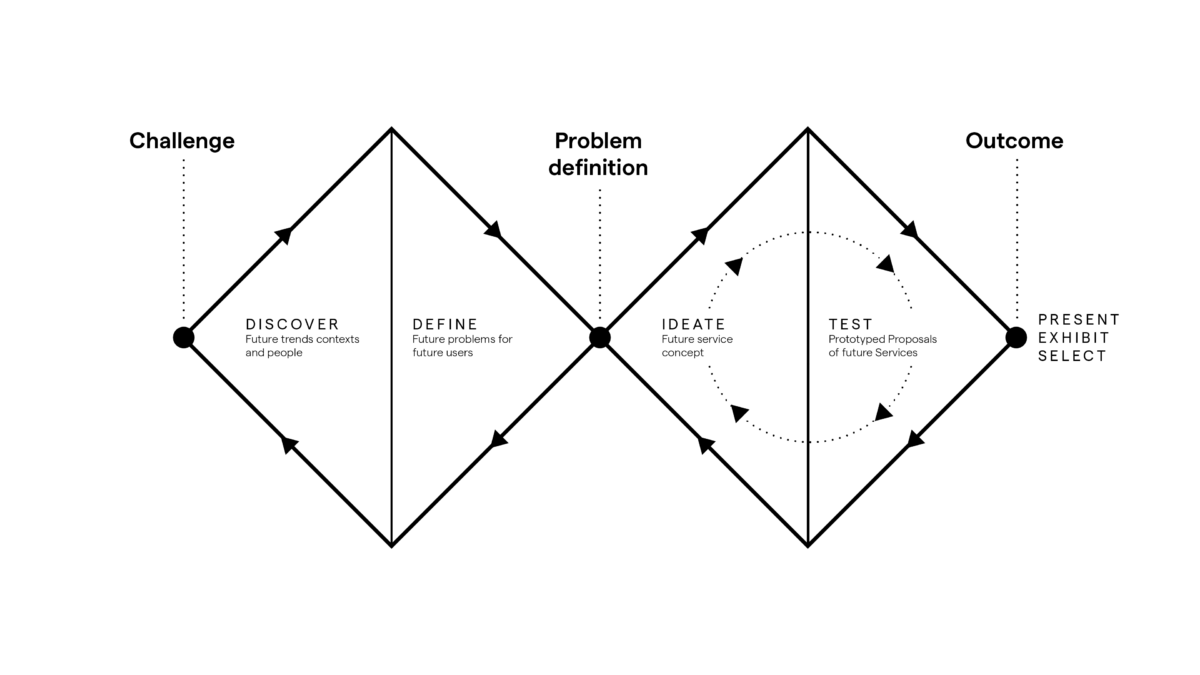

The project guide followed the double diamond framework (developed by the Design Council) and its four stages: discover, define, develop and deliver. However, the phases were adapted to the students and the client’s needs, so they had to discover & define, ideate, test and present and exhibit.

For the entire duration of the projects, the students were followed by a tutor who had weekly review sessions with them. There were also two main checkpoints with the RCA Service Design tutors: the interim review and the final review, completed with an online submission and selection before the shortlisted projects were able to present their work to the client

Activities

Activity 01:

Discovery and definition

The students first activity was discovery and definition. This corresponds to the first half of the Double Diamond, which includes the research (Discover), followed by the definition of the problem and the creation of a refined brief specific to the students project interests (Define).

Their brief was just a starting point, but the lab team was expecting the students to be able to define their own brief by identifying a specific problem statement. Starting from the design challenges that had been proposed to them, the students went through a research phase, exploring the problem by conducting primary research and desk research. These often included surveys, interviews, and reading of articles, papers and books. They then tried to identify the most crucial and relevant issues to consider in their selected area of interest, and they established their point of view on the topic.

As part of the definition phase, the students used the insights they collected from the research, to identify their scenario of action. For this scenario, they outlined who is involved, as well as the organisational and systemic context of the problem to be solved.

While creating their own briefs, each team developed their own personas and detailed the objectives each person may have. They analysed the research findings and developed a set of critical questions and clear design objectives to create solutions that take into account the different stakeholders and their goals, as well as the nature of the overall system into which those stakeholders fit.

Activity 02.

Ideation

Once the students had defined their problem statement and brief, they started what is called the ‘Develop’ phase in the Double Diamond. This phase includes both ideation and prototyping. Here the two activities are divided, but in reality, it was an iterative process of ideation, prototyping and testing. This way of working is part of the service design process, inspired by the build, measure, learn strategy from the ‘lean startup’ approach.

Following this way of working, students were continually creating concepts and testing them quickly, so they could refine them and then re-test. For the ideation activities, students focused on the generation of concepts, reflecting on how they would be executed, by whom, for whom, and to what end.

To make sure these concepts would generate the value they wanted to create, the students consulted with experts and key stakeholders. They also visualised their ideas through the use of service design tools, such as user journeys and blueprints. Once the concept was defined, the students were asked to prepare a prototyping plan, to test the service fully or partially, and collect feedback from users and stakeholders to help them refine their ideas.

Activity 03.

Test

Students were encouraged to be creative in finding ways to prototype their concepts rapidly. Part of the challenge was to create prototypes that did not require much time and resources, but that would still allow them to validate their concepts with stakeholders and users, get meaningful feedback and understand how to improve them. The other challenge was that for ‘Far Future’ concepts students had to test elements of the service that were in some way reproducible using today’s technology and only with existing users rather than future ones. This meant being imaginative about finding alternative ways to test their hypotheses. During the prototyping phase, the students presented their progress at an interim review. This was a great opportunity for them to receive feedback and advice from the tutors on how to test their concepts further and how.

Each team developed their own methods to test their services, from clickable interfaces, to simulated AI chatbots and physical prototypes. The students worked autonomously to recruit testers; they set up interviews and workshops and used both physical and digital tools to communicate their concepts.

Active 04.

Present

At the end of their projects, the students had a final review with the programme’s panel of tutors. This was their chance to present their work in its entirety, from the research they conducted to the service they created and the testing with the stakeholders.

Each service was also documented with a detailed blueprint, a viable deployment plan and a comprehensive narrative. The lab team also asked the students to describe a business model to demonstrate that the service could be commercially feasible, either through return on investment or return on social capital.

It was a great opportunity for the students to collect feedback from the tutors, and to reflect on the details of their concepts. Each team was given 10 minutes to present their work, followed by questions from the tutors and feedback.

Activity 05.

Exhibit

This last activity was not directly connected to the project with the client. But, it is important to mention that at the end of the term all the students were invited to present their work in the ‘work in progress’ show at the RCA.

Each team communicated their service proposition in a way that allowed the audience to understand and experience the service. For the selected projects, it was an excellent opportunity to test their concepts and collect feedback from the general public.

Selecting studio projects

Activities

Activity 01.

Submission and shortlisting

At the end of their projects, the lab team asked the students to submit their work through an online form. They were asked to highlight what the concept was about, its key benefits, the key findings of the background research, the problem they were trying to solve, and for which users. They were also asked to describe the future scenario and context of the project, and provide an overview of the strategy for further development and prototyping.

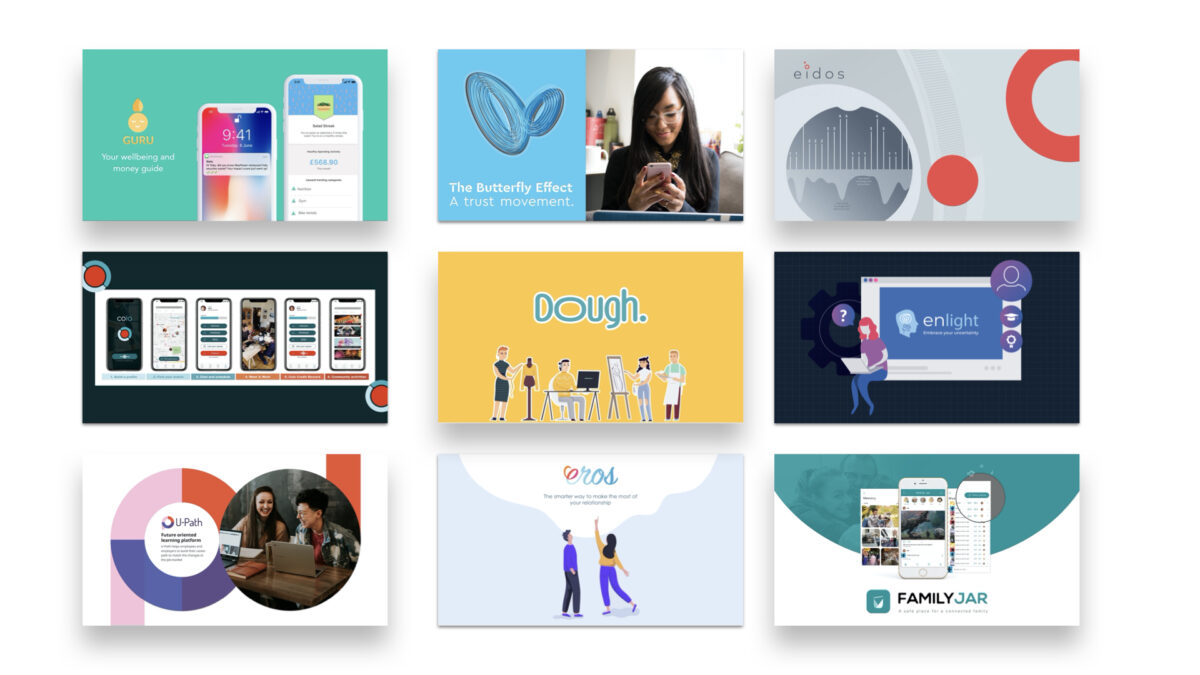

Using this form, the lab team was able to compare the projects, and understand which ones were more aligned with the client’s current strategy and what value they would bring to Koa Health. Then, the lab team with the client, shortlisted ten teams from the second year, and two teams from the first year to present their work to the rest of the organisation.

Activity 02.

Presentation to the client

These teams were invited to present their work at the client’s headquarters, in front of the whole team. During the presentations, the students were asked questions about the services they created and what plan they had for further development and testing of an MVP (Minimum Viable Product)

The lab team then asked each member of the client’s team to fill an online survey to assess each project based on how relevant it was for their strategy and why, how clear and exciting the idea was, and how aligned it was with the client’s OKRs (Objectives and Key Results).

The criteria for the selection of the student projects were based on how aligned the concepts were with the client’s strategy and their selected market. At this stage, the lab team was looking for projects that could integrate with the client’s existing range of products and services and that provided value in the area of health, happiness and wellbeing.

Then, they selected three teams from the second year, which were invited to continue their work as their final year project, with the support of the client and xploratory. They also selected one project from the first year, which was integrated into their work with the lab explorations.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Phase 2: Explore service visions

Unit 2: Conducting Studio Explorations

Involving the RCA students

In this unit:

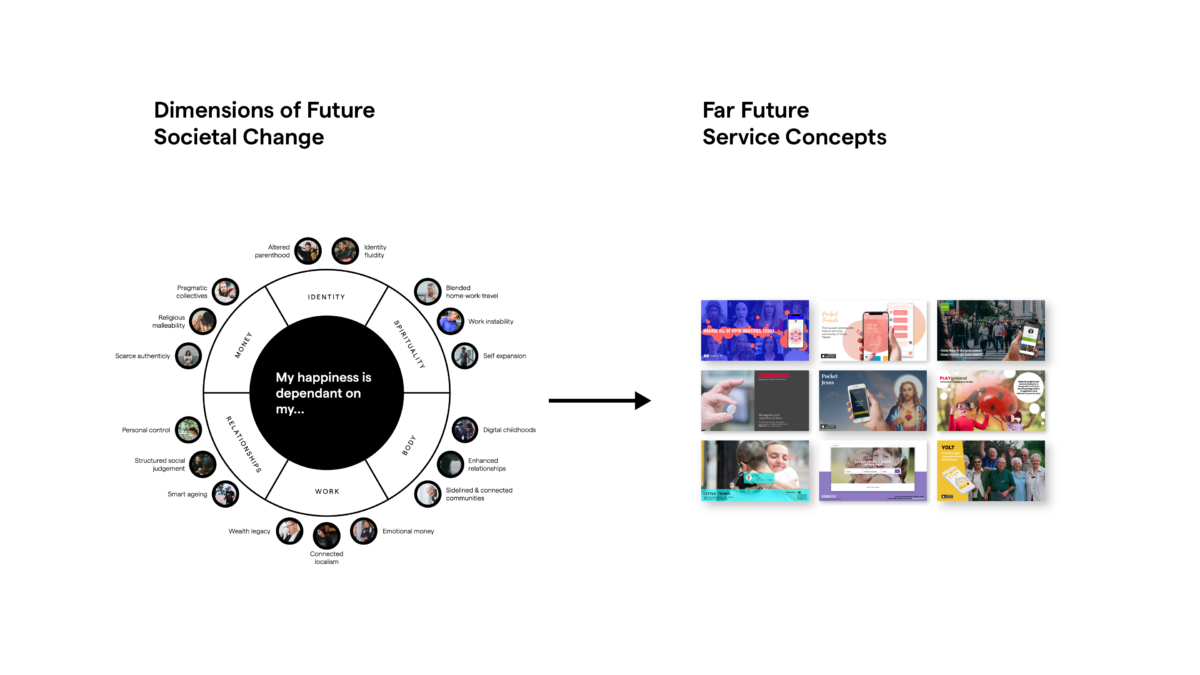

The lab team worked to develop visions of ‘far future’ services that responded to the scenarios and design challenges created in the previous phase. The aim of the future service visions was to allow the entire organisational team to imagine the tangible possibilities of a future that may arise.

The visions grounded the team in a common portrayal of the future and provided insight into the implications and the emerging topics that otherwise would have been too abstract. In other words, the visions are not simply sketches of potentially implementable services, they are tools for exploration which inform the collective imagination.

The key goal of this unit of work was to create visions that are diverse enough to scan the landscape and provoke conversation about the huge diversity of potential issues and opportunities in the future.

Overview

For the lab explorations, the lab team decided to focus on more extreme scenarios and their design challenges. An exploration is the process of creating service visions around a scenario and discussing the topics that emerge.

At this stage, they were not heavily focussed on finding strategic alignment with the client. Instead, they were still in the exploration phase, trying to identify opportunities around the future of health and happiness.

The legitimacy of the visions was not essential at that point because the explorations were used as a mechanism to inspire the client to think about opportunities and prioritise different directions for the process.

The prioritisation of visions was based on what had more potential and what was more provocative and exciting. Often, these visions deliberately articulate provocative or even implausible caricatures of services because provocation and implausibility can stimulate the dialogue that is necessary for the emergence of new strategies.

The value of the scenarios was abstract, making it challenging to understand what kind of role the client could have in the contexts they had depicted.

This is why the exploration process first grounds the discussion by visualising future service visions that might exist within the scenarios and creating corresponding narratives. The lab team did not create anything of high-fidelity; instead, they used simple storyboards and sketches to make the abstract exploration of future scenarios more tangible and accessible for the client.

By creating these visions and visualising them, the lab team was uncovering the potential within each of the societal dimensions of change and identifying the emerging themes that may be relevant.

In other words, at this point, they were not testing the visions, they were testing the themes. By making those ideas tangible, the client was able to engage with those discussions and understand which directions and areas had more potential, regardless of the client’s current strategy.

In sum, the explorations helped expand the client’s understanding of emerging themes and helped them prioritise topics.

Briefing the Lab

The briefing stage for the lab was not only to write an effective guide for the next stage but also to collect all the material, organise it and reflect on it, before moving on.

As already mentioned, the lab only focused on the scenarios and challenges derived from the trends analysis and extreme users research, which formed the ‘Far Future’ time horizon. Strategic alignment was not a priority in this phase because the lab team was exploring the themes further by developing future service visions, to then identify opportunities.

Activities

Activity 01.

Review of design challenges

The lab team started by synthesising all the material they had on the scenarios and challenges. With that, they organised a third workshop with the organisation to assess the design challenges for the lab, but also to prioritise themes and scenarios for the studio briefs, which will be discussed in detail in the Studio Explorations stage.

During the workshop, the lab team reviewed all the steps of their process, from objectives and methodology, to the research on trends and the outputs of the second workshop. They then presented the work done with the extreme users, and the process they followed to create future personas and extreme scenarios.

Once everyone had a clear understanding of these scenarios, they gave each participant a sheet with all the design challenges. They encouraged all participants to share their comments and questions about the challenges to help them understand how to refine them.

The last task was to vote on the challenges. The goal was not to make a selection, but to gauge what themes the client seemed to be more curious about, and what kind of opportunities they were considering.

With this in mind, the lab team asked the client to take into consideration what they found more interesting, what they were not familiar with but had potential to be explored, what challenges would best support their strategy and which scenarios they found more provoking.

Activity 02.

Refine the design challenges

Based on the voting results and discussions with the client, the lab started to adjust challenge questions and reframe the topics. By understanding what the client found exciting and provoking, they were able to be more precise in defining problems to frame the briefs around.

At this point, the lab team made an important observation about the risk of being too simplistic when imagining the future, for example, focusing only on utopian or dystopian perspectives. This concern also encouraged the initial decision to engage with extreme users.

To overcome this problem, the lab team focused the design challenges on the needs and goals of the future personas, as the starting point for creating the explorations, instead of focusing on the technologies or the extreme consequences of emerging trends.

Creating Service Visions

After the briefing, the lab team was then ready to start envisioning future concepts. These visions were representing what kind of services might emerge in the extreme scenarios they created and how those concepts would help address the design challenges they identified.

The process to create these concepts was mainly an ideation exercise, as they wanted to explore the potential behind each key theme, and they did that by imagining services that were meeting specific needs and goals related to the happiness of the people who will inhabit those futures.

Activities

Activity 1:

Brainstorm and ideation

With the design challenges refined and agreed with the client, the lab team started brainstorming ideas for each design challenge. First, they immersed themselves in the future context, by using their signals and trends research to understand the implications of change. Then, they tried to empathise with the future persona, imagining what needs and goals would emerge in those scenarios.

Using their knowledge on emerging technologies and other trends that could affect each extreme scenario, they started to brainstorm simple ideas that consider the needs identified and respond, in whole or in part, to the main design challenge.

The ideas at this stage consisted only of a name and a short description. There was no assessment in this process. It was purely an ideation exercise aimed at imagining what services could emerge based on those extreme future scenarios. In some cases, the ideas were immediately problematic but were kept because there was potential for them to exist in the future and could therefore enrich conversation or influence other service visions.

The lab team created 87 ideas, including the ideas from the Envision Sprint with the client.

Activity 02:

Discussion of implications

Before starting the visualisation of ideas, the lab team had an internal prototyping session. During this activity, they tried to explore the implications of their ideas by discussing them internally. This helped them reflect on which concepts would have more impact for the future persona and whether they respond to the design challenge.

They later realised that a beneficial activity that they could have done at this stage was to use the future wheel to explore the direct and indirect consequences of each idea. This would have helped them cross-reference the concepts and uncover potential interplay between them and possible combinations of multiple ideas.

The team plans to include the future wheel as an activity for this stage in future projects.

Activity 03.

Visualisation and prototyping

With more clarity on which ideas to prioritise for the prototyping, the lab team started with the creation of a simple template that would allow them to communicate the concepts quickly, requiring minimal resources.

At this stage, they were not looking for high-fidelity prototypes, as they were not interested in the validation of the idea per se, but more in the exploration of the opportunities and impacts behind each design challenge, and more generally, the key theme.

The template included a name and a tagline, a short description, a simple sketch illustrating the idea, the critical elements involved, a storyboard showing how the user experience would look, and a hero image. They used this template to visualise 33 of their ideas, which were chosen based on what seemed strategically significant and those that responded best to the design challenges.

So, for each idea, they completed the template working from the end of the user story, considering what happiness means for the future persona. They imagined the future persona achieving that happiness after experiencing their service. Then, they worked backwards to define the rest of the journey, identifying the critical elements of the service vision, the main features and the benefits.

With this process, they produced clear and straightforward narratives, showing how the concepts can contribute to the happiness of the users.

These ideas, their representation and subsequent discussion constitute what the lab team called “explorations”. They are the imagined service visions that could potentially emerge in the future as ways to respond to future problems and the implications they may have.

Active 04.

Extreme user testing

The lab team later understood the importance of having a testing phase at this stage where the explorations could be reviewed and reflected on by extreme users. In future projects this step would be included.

Participants would realise these concepts are only provocations that are set in a distant future. However, they would be able to see the kind of impact these explorations may have on their future happiness.

The format of this testing could be interviews, a workshop or even an exhibition. Getting feedback from the general public would be valuable. However, it is preferable to have extreme users engage with the concepts to observe their reactions. These extreme users can be those that have been already interviewed.

Activity 05.

Evaluation of the explorations

After the prototyping activity, the lab team started to prepare a fourth workshop with the client to introduce them to the explorations. As mentioned previously, the lab team was more interested in an assessment of the topics and areas, rather than specific feedback on the concepts.

They used the ideation of visions as a way to explore and present to the client the potential of each theme and also to uncover the topics that expand, inspire and provoke the client’s thinking — which was the main objective of the collaboration.

In this workshop, they held what they called a Service Vision Safari. This was an activity in which they exhibited their visions by printing them out and attaching them to the walls of the client’s office. They also printed the future personas profiles, so that the client could easily identify what areas they were trying to address for each concept.

Then, they asked the participants to familiarise themselves with the ideas, reflect on them, and discuss them, by making comments and asking questions. This activity provided them with many insights and suggestions for improvement.

Once the client’s team was familiar with all the concepts, the lab team asked them to vote, either for or against continuing to explore that service vision. The client team were asked not just to consider the viability, feasibility or desirability of the idea, but the opportunities that the idea uncovered and the topics that had the most potential.

Selecting concepts for the next phase

The lab team and the client reviewed all the concepts, voted and selected their priorities based on client strategy, plausibility, impact, provocativeness and ease of prototyping. These selected concepts were brought forward to the next stage.

Activities

Activity 01.

Criteria for selection

The lab team’s primary reference for selection were the voting results from the workshop with the client, although they also used their feedback to refine the ideas and combine some of the visions.

Nevertheless, other factors influenced their decision. First, by considering the combination of some visions, they uncovered interesting topics worth exploring further, even if a single vision on its own was not valuable.

Second, as the lab team approached the next phase where they would consider the alignment of the visions with the client’s strategy, they assessed the plausibility and impact of the concepts in terms of how they could influence happiness. Other considerations were also made on whether some topics would be addressed better by the students, or if the ideas could be prototyped quickly.

Lastly, they tried to identify which concepts could raise valuable discussion for the client and therefore had more value to collect insights.

They also grouped the concepts using alternative classifications,(i.e theme clustering). In this way, they made sure they covered most of the essential discourse that emerged from the explorations.

Activity 02.

Comparison of results

By taking this more analytical approach to the selection, they were able to define the ten concepts to take forward. Each one brought a valuable discussion and a topic to explore.

All these considerations were then visualised in the form of charts so that the lab team could see which concepts met most of the criteria and which of the emerging areas and topics were the most inspiring and impactful.

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Phase 2: Explore service visions

Unit 2: Conducting Studio Explorations

Involving the RCA students

An overview of our design approach

The work of the first phase was to expand the organisation’s imagination of what the contexts of the future may look like by creating scenarios based on trends and users.

This second phase ‘Explore Service Visions’ is about expanding the organisation’s collective imagination around the services that could emerge in future contexts by creating concepts of future services.

The purpose is not to immediately start designing the more plausible or preferable services, but instead provoke deeper consideration of the implications.

In doing so, the organisation is challenged to answer questions about their role creating, shaping or managing change in the world. It can be seen as a thought experiment that challenges the organisation to deepen their understanding of their values and strategies while also deepening their imagination of potential modes of operation within any given future scenario.

The theory

For this design approach, the lab ideated concepts of future services based on the scenarios developed in the first phase. This meant empathising with the future users depicted in each scenario, imagining them and the context that has emerged around them, and then responding to the design challenges by ideating services that could be good or bad. These ideas were then made more concrete and tangible, which enabled the team to open the discussion with the organisation about the implications of the concepts and organise the subsequent stages of the process.

We refer to these future service visions and their ensuing discussion, as ‘explorations’.

The process

The second phase is divided into two units:

- the work the team did as ‘the lab,’;

- the work done by the students as ‘the studio’.

While the lab team was in the ideation phase, it was the perfect time to turn the research into briefs and start involving the students in the project.

The value of the studio work was significant – it meant having more than 80 students researching, ideating and testing concepts. They were also engaging with hundreds of people through interviews, workshops and collaborations. Moreover, since the lab team kept the briefs open for the students, they also helped expand the understanding of the societal dimensions of change.

Before creating the briefs for the students, the lab team did their own round of explorations first, so that they could build knowledge to transfer to the students.

Their explorations were concepts of future services, which enabled them to investigate the opportunities that could emerge around each dimension of change, get feedback from the client, and have criteria to prioritise the key themes. The lab team based these explorations on the extreme scenarios, which detail the needs of future personas set at the ‘Far Future’ time horizon.

The lab team then initiated a similar process for the students, except designing for the ‘Near Future’ time horizon. Between the lab and the studio, there was a mutual exchange of knowledge, the lab team would give them insights on the theme and how to create explorations, and the students would give back their points of view, which built alternative perspectives of the themes.

While the process for the lab team was a more experimental approach to test assumptions quickly, the students applied a more traditional service design process, following the guidelines given by the MA Service Design Programme, inspired by the Double Diamond model.

Phase 2: Explore service visions

This second phase comprises two units. By creating concepts of future services, the aim is to expand the organisation's collective imagination around the services that may emerge in future contexts

Would you like to know more?

Let's find the place to think, the freedom to challenge and the capability to act on real change. Together.

Edit is a lifestyle service that helps you edit things in and out of your life through enriched tracking and mini-experiments.

What’s the problem?

While there are seemingly endless resources, research, and tools for building healthier habits, people continue to struggle with a sustained change in behaviour over time. When it comes to health and wellbeing, people tend to struggle with four main areas: control, accountability, personalisation, and reward.

Control:

People usually begin a journey to change behaviour with a fundamental misunderstanding about what it takes to accomplish such a thing. Many of our behaviours are deep-seated and are significantly more challenging to change than perceived. This inevitably leads to what we refer to as a relapse and a feeling of helplessness. To be more specific, people feel that they lack control because they lack awareness and context for their behaviour.

Accountability:

Ultimately, most people accomplish things that they feel accountable for achieving. When it comes to most wellbeing goals, most people don’t have a high enough accountability level to change behaviour in a sustainable way.

Personalisation:

While there are many approaches to creating a new habit, unfortunately, many are generic and don’t consider human beings’ nuances. Things like personality, culture, and life experience make up who we are and how we behave, which is why individuals need a personalised approach to behaviour change.

Reward:

Reward, recognition, and incentives all play an essential role in long-term behaviour change, but all too often, those things come in a delayed manner. The lack of immediate reward causes many people to relapse towards old behaviours much sooner without the motivation to make a new attempt.

The four areas briefly described above came from research conducted with people trying to change addictive behaviour. Specifically, we worked with people trying to quit smoking to understand behaviour change on a more intense level. As one of our research participants said, “I am a single mother of 4, working in the male-dominated world of finance, and the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life was quitting smoking.” While we also worked with leading researchers and experts in behaviour change, it ultimately was the work with these “extreme” users that provided the most insight into Edit’s development.

How ‘Edit’ responds

Edit responds to the above challenges by breaking the traditional behaviour change cycle and forming a new continuous cycle that focuses on action and learning, rather than relapse. We designed Edit as a modular service that provides people with options for engaging in a continuous cycle of action and learning to build healthier habits over time.

Chat, Story, People, Explore:

Edit consists of four main service components: chat, story, people, and explore. Certainly, we believe that the service is most potent when engaging with some combination of all four service components, but Edit also accommodates the person interested in some. These components are driven by enriched tracking that uses multiple sources of data to help users better understand the impact of their daily actions on their well-being.

Chat:

Through the Edit Bot, users can provide context to their actions during the day, ask questions to help customise edits, and receive quick updates on progress.

Story:

Through a feed of insights and accomplishments, users can socially share progress and choose new edits to try based on newly developed insights.

People:

By connecting with people in the Edit Community, users can learn from others who are going through similar journeys—inspiring them to try different edits.

Explore

Through a marketplace of organisations (example: NHS) and individuals, Edit users can discover new edits to try, sell (or gift) their own edits, and begin other behaviour change journeys with confidence.

To illustrate how these features can work together, it is useful to look at them in the context of one person’s journey using the service.

What we

learnt

Although most people are continually thinking about how they can be healthier, they require a drastic event (medical reasons, family reasons, or intense life experiences) to trigger an actual change in long-term behaviour. Through this project, we’ve found that there are some less severe ways that more people can build healthier habits. By understanding the impact of daily actions and creating new and personalised rituals (edits), people are able to build enough resiliency to not only survive a relapse in behaviour, but turn it into a meaningful moment of learning. That is the key to consciously building healthy habits that will increase one’s overall wellbeing.

The Value of Behaviour Change

While we discovered the power of enriched tracking and small daily edits in changing behaviour, it is also clear that behaviour change has a variety of value. Of course, it has value to the individual and those people directly in their lives. However, and more interestingly, it has value to society as a whole. Edit ultimately attempts to solve the challenge: how might we connect a person’s actions with an immediate and individualised reward with a more significant impact on society’s overall wellbeing?

By moving habit formation away from generic models to giving people full agency over their wellbeing, as they define it, we can create a massive and highly intelligent database that understands behaviour change on an incredibly granular level at scale. What we do with that is the critical question. Suppose we can leverage this theoretical intelligent database appropriately. In that case, we could create communities centred on wellbeing, which may ultimately improve population health and reduce unnecessary stress on healthcare systems.

Our new direction of exploration

The entire premise of Edit is that people have an open and transparent relationship with the idea of behaviour change. Unfortunately, in our culture, a behaviour change is often seen as criticism, failure, or even an embarrassment. As trends around health and wellbeing continue to grow, we wonder how something like Edit could be positioned to shift the societal mindset towards behaviour change fundamentally.

Rhea Belani

Related to ‘Edit’

Scenarios

Personal control

Devices quantify and measure all aspects of the people’s lives and body amplifying obsessive behaviours. People’s personal identity becomes more based on an idealised virtual version of oneself rather than your existing reality.